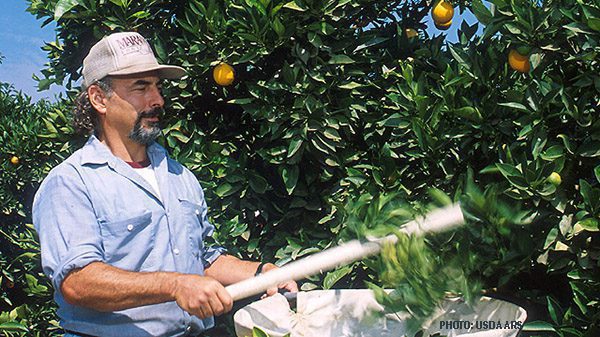

Matthew Blua, entomologist at University of California at Riverside, beats an orange tree to shake loose glassy-winged sharpshooters.

Photo by Peggy Greb.

The EATS Act—there are more than one of them. It is, as Dan Flynn of Food Safety News observes, “an often-used name for legislation regarding certain food topics.”

This one stands for “Ending Agriculture Trade Suppression,” a bill introduced in the Senate in June by Sen. Roger Marshall (R-KS). Rep. Asley Hinson (R-IA) sponsored the same legislation in the House later that month.

The issue is meat production—and how far states can regulate it. It is the aftermath of a Supreme Court decision in May that upheld Proposition 12, a legislative amendment passed by the voters in California in 2018 stipulating certain standards of humane treatment for livestock animals. The crux of the issue: the law imposes those standards on any animal product that is sold in the state, whether it came from California or not. This law was challenged, but the Supreme Court upheld it.

“Congressional Republicans stated they introduced the EATS Act in part to invalidate Proposition 12, a California law setting certain standards for eggs, pork, and veal sold in the state,” according to a legislative analysis by the Brooks McCormick Jr. Animal Law and Policy Program of the Harvard Law School.

Unsurprisingly, the National Hog Farmer supports the EATS Act.

Equally unsurprisingly, the Humane Society of the United States condemns it.

This all might appear to be of marginal interest to the produce industry, but it may be more.

The Harvard analysis strongly criticized the proposed law for reasons that are quite relevant:

“Almost every state imposes laws regulating the importation of agricultural products containing certain pests, diseases, or invasive species. Oftentimes, these regulations require treatment, inspection, certification, quarantine, or embargo of certain products entering the state. The EATS Act could prohibit these requirements, leaving producers more vulnerable to pests like the glassy-winged sharpshooter and the emerald ash borer and to diseases such as phony peach disease.”

The poetically named glassy-winged sharpshooter “causes Pierce’s Disease,” notes the analysis, “which afflicts grape crops by interfering with the plant’s water collection system, ultimately causing the vine to die. The insects also can affect citrus trees, almonds, and other crops.”

Researchers have estimated that Pierce’s Disease costs California alone over $100 million in annual damages to the grape and wine industry. Accordingly, public spending to combat the disease is significant. California and other states like Oregon, which also boast large wine industries, have implemented import restrictions on agricultural articles that may be carrying the pest––such as inspections, quarantines, and prohibitions on the interstate shipment of certain plants. The EATS Act thus may interfere with those states’ ability to enforce such regulations” by invalidating current requirements for the preharvest treatment of out-of-state agricultural products to kill the sharpshooter. “Further, the EATS Act could prohibit an outright ban on the importation of infested agricultural products carrying the insect.”

The same is true of phony peach disease (PPD): “Because treatment options for PPD are limited, efforts to prevent transmission are critical to reducing the spread of the disease. Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and other states have implemented regulations to protect fruit stocks from PPD. These PPD regulations might not survive challenges under the EATS Act.”

Personally, I doubt that the EATS Act will ever become law: it is difficult to imagine that it will pass both houses of Congress and be signed by President Biden. But its sponsors can go back to their constituents in the meat industry and say that at least they tried to do something.

The EATS Act—there are more than one of them. It is, as Dan Flynn of Food Safety News observes, “an often-used name for legislation regarding certain food topics.”

This one stands for “Ending Agriculture Trade Suppression,” a bill introduced in the Senate in June by Sen. Roger Marshall (R-KS). Rep. Asley Hinson (R-IA) sponsored the same legislation in the House later that month.

The issue is meat production—and how far states can regulate it. It is the aftermath of a Supreme Court decision in May that upheld Proposition 12, a legislative amendment passed by the voters in California in 2018 stipulating certain standards of humane treatment for livestock animals. The crux of the issue: the law imposes those standards on any animal product that is sold in the state, whether it came from California or not. This law was challenged, but the Supreme Court upheld it.

“Congressional Republicans stated they introduced the EATS Act in part to invalidate Proposition 12, a California law setting certain standards for eggs, pork, and veal sold in the state,” according to a legislative analysis by the Brooks McCormick Jr. Animal Law and Policy Program of the Harvard Law School.

Unsurprisingly, the National Hog Farmer supports the EATS Act.

Equally unsurprisingly, the Humane Society of the United States condemns it.

This all might appear to be of marginal interest to the produce industry, but it may be more.

The Harvard analysis strongly criticized the proposed law for reasons that are quite relevant:

“Almost every state imposes laws regulating the importation of agricultural products containing certain pests, diseases, or invasive species. Oftentimes, these regulations require treatment, inspection, certification, quarantine, or embargo of certain products entering the state. The EATS Act could prohibit these requirements, leaving producers more vulnerable to pests like the glassy-winged sharpshooter and the emerald ash borer and to diseases such as phony peach disease.”

The poetically named glassy-winged sharpshooter “causes Pierce’s Disease,” notes the analysis, “which afflicts grape crops by interfering with the plant’s water collection system, ultimately causing the vine to die. The insects also can affect citrus trees, almonds, and other crops.”

Researchers have estimated that Pierce’s Disease costs California alone over $100 million in annual damages to the grape and wine industry. Accordingly, public spending to combat the disease is significant. California and other states like Oregon, which also boast large wine industries, have implemented import restrictions on agricultural articles that may be carrying the pest––such as inspections, quarantines, and prohibitions on the interstate shipment of certain plants. The EATS Act thus may interfere with those states’ ability to enforce such regulations” by invalidating current requirements for the preharvest treatment of out-of-state agricultural products to kill the sharpshooter. “Further, the EATS Act could prohibit an outright ban on the importation of infested agricultural products carrying the insect.”

The same is true of phony peach disease (PPD): “Because treatment options for PPD are limited, efforts to prevent transmission are critical to reducing the spread of the disease. Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and other states have implemented regulations to protect fruit stocks from PPD. These PPD regulations might not survive challenges under the EATS Act.”

Personally, I doubt that the EATS Act will ever become law: it is difficult to imagine that it will pass both houses of Congress and be signed by President Biden. But its sponsors can go back to their constituents in the meat industry and say that at least they tried to do something.

Richard Smoley, contributing editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 12 books.