A recent article on Slate by Tim Requarth asked, “Is there anything to the panic over ultraprocessed foods?”

As Requarth notes, Michael Pollan’s celebrated but controversial 2008 book In Defense of Food urged readers not to eat any foods that their great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize. (For me, that rules out jackfruit, soursop, and feijoas, not to mention avocados, kiwifruit, and papayas.)

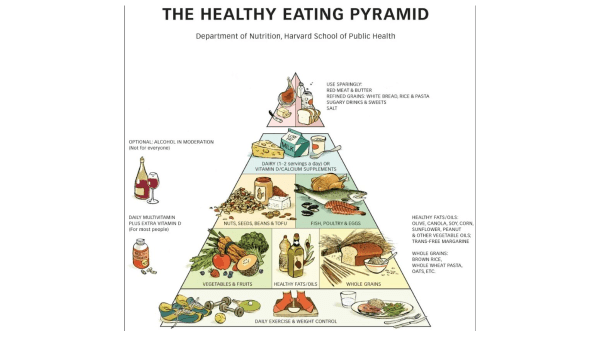

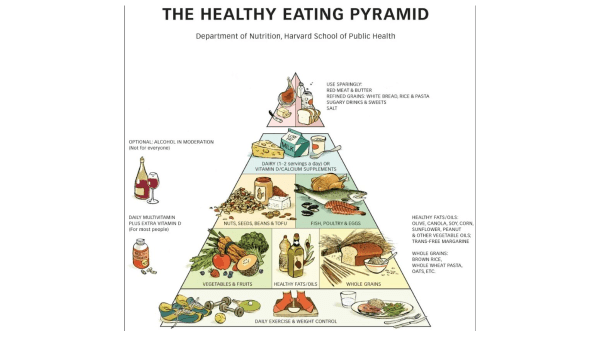

Pollan’s book inspired Brazilian public health researcher Carlos Monteiro to upend the famous healthy eating pyramid.

By this model, you’re supposed to eat lots of foods at the base of the pyramid—healthy fats and oils, whole grains, and of course fruits and vegetables—and very little of the food at the top, such as red meat, sugar, and refined grains.

Monteiro and his colleagues proposed three very different categories: “Unprocessed or minimally processed foods (group 1), processed culinary and food industry ingredients (group 2), and ultra-processed food products (group 3).”

Fruits and vegetables, of course, fit into category 1, as do whole grains. Pastas made only with grain and water fit into category 2. All breads, cheeses, and canned vegetables are in category 3. So are fats and oils—even the “good” ones at the base of the food pyramid.

Monteiro and his colleagues come up with some surprising conclusions. “‘Table’ sugar . . . is less of an issue than sugars and syrups added to ready-to-consume processed products, one example being soft drinks. The fact that any type of sugar is chemically identical is not the point. It is above all processing that leads to over-consumption of sugars and syrups.

“Secondly, bread: all types of bread are often identified as healthy, or else a distinction is made between wholegrain breads, and breads made from refined ‘white’ flour. Our view is that the classification of bread (usually meaning wheat bread) as a group 3 product, is conceptually and factually correct. Also, as consumed, bread, which is itself fairly energy-dense, is often a vehicle for table fats and other energy-dense products, frequently in the form of sandwiches.”

For Monteiro and his colleagues, the villain is the processing itself, although, they write, “this paper is not suggesting that healthy diets are composed only of unprocessed and minimally processed foods and processed ingredients. The issue is one of proportion.”

The conclusion, nevertheless: “Those actors responsible for food and nutrition policies need to use all possible methods, including legislation and statutory regulation, to halt and reverse the replacement of minimally processed foods (group 1) and processed culinary ingredients (group 2) by group 3 food products.”

Although the produce industry can live comfortably with that, somehow the NOVA system seems off-track: there seems to be something wrong with lumping whole-wheat bread together with fish sticks and chicken nuggets.

In the end, I agree with Requarth: “What disheartens me about the crusade against [ultraprocessed foods] is its puritanical streak: the notion that a diet of convenient, delectable, and chemically complex foods must be too good to be true, and that we should, in response to this concerning-but-uncertain evidence, avoid the chips-and-snacks aisle at the grocery store like it contains poison. This puritanical rhetoric is amplified for parents, and mothers in particular bear the weight of judgment when they turn to store-bought baby food rather than spending endless hours pureeing vegetables on a Sunday afternoon.”

His point is important. People do not like being forced into what’s good for them (one lesson that should have been learned during the pandemic). I also abhor the emotional toxic waste that guilt-mongering generates. There is good reason to promote consumption of healthy foods like fruits and vegetables. But a crusade against ultraprocessed foods is, in the long run, likely to backfire.

A recent article on Slate by Tim Requarth asked, “Is there anything to the panic over ultraprocessed foods?”

As Requarth notes, Michael Pollan’s celebrated but controversial 2008 book In Defense of Food urged readers not to eat any foods that their great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize. (For me, that rules out jackfruit, soursop, and feijoas, not to mention avocados, kiwifruit, and papayas.)

Pollan’s book inspired Brazilian public health researcher Carlos Monteiro to upend the famous healthy eating pyramid.

By this model, you’re supposed to eat lots of foods at the base of the pyramid—healthy fats and oils, whole grains, and of course fruits and vegetables—and very little of the food at the top, such as red meat, sugar, and refined grains.

Monteiro and his colleagues proposed three very different categories: “Unprocessed or minimally processed foods (group 1), processed culinary and food industry ingredients (group 2), and ultra-processed food products (group 3).”

Fruits and vegetables, of course, fit into category 1, as do whole grains. Pastas made only with grain and water fit into category 2. All breads, cheeses, and canned vegetables are in category 3. So are fats and oils—even the “good” ones at the base of the food pyramid.

Monteiro and his colleagues come up with some surprising conclusions. “‘Table’ sugar . . . is less of an issue than sugars and syrups added to ready-to-consume processed products, one example being soft drinks. The fact that any type of sugar is chemically identical is not the point. It is above all processing that leads to over-consumption of sugars and syrups.

“Secondly, bread: all types of bread are often identified as healthy, or else a distinction is made between wholegrain breads, and breads made from refined ‘white’ flour. Our view is that the classification of bread (usually meaning wheat bread) as a group 3 product, is conceptually and factually correct. Also, as consumed, bread, which is itself fairly energy-dense, is often a vehicle for table fats and other energy-dense products, frequently in the form of sandwiches.”

For Monteiro and his colleagues, the villain is the processing itself, although, they write, “this paper is not suggesting that healthy diets are composed only of unprocessed and minimally processed foods and processed ingredients. The issue is one of proportion.”

The conclusion, nevertheless: “Those actors responsible for food and nutrition policies need to use all possible methods, including legislation and statutory regulation, to halt and reverse the replacement of minimally processed foods (group 1) and processed culinary ingredients (group 2) by group 3 food products.”

Although the produce industry can live comfortably with that, somehow the NOVA system seems off-track: there seems to be something wrong with lumping whole-wheat bread together with fish sticks and chicken nuggets.

In the end, I agree with Requarth: “What disheartens me about the crusade against [ultraprocessed foods] is its puritanical streak: the notion that a diet of convenient, delectable, and chemically complex foods must be too good to be true, and that we should, in response to this concerning-but-uncertain evidence, avoid the chips-and-snacks aisle at the grocery store like it contains poison. This puritanical rhetoric is amplified for parents, and mothers in particular bear the weight of judgment when they turn to store-bought baby food rather than spending endless hours pureeing vegetables on a Sunday afternoon.”

His point is important. People do not like being forced into what’s good for them (one lesson that should have been learned during the pandemic). I also abhor the emotional toxic waste that guilt-mongering generates. There is good reason to promote consumption of healthy foods like fruits and vegetables. But a crusade against ultraprocessed foods is, in the long run, likely to backfire.

Richard Smoley, contributing editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 13 books.