It’s starting to look like a glitch in the Matrix.

Yet again, agricultural leaders are calling upon Congress to adopt some version of the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, which passed twice in the House of Representatives with bipartisan support, but which the Senate has so far failed to act on.

The law would go some way toward solving the acute crisis in agricultural labor.

I am not shrewd enough a politico to try to calculate the bill’s chances this time around, and I’m not a betting man, so I will avoid giving odds.

But a recently released report from USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS), entitled Adjusting to Higher Labor Costs in Selected U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Industries, by Linda Calvin, Philip Martin, and Skyler Simnitt, outlines the direction of current trends.

The report doesn’t contain any bombshells, but it does summarize the present situation concisely.

We learn, for example, that “farm labor wage rates—measured by real farm earnings—increased faster than nonfarm rates (16 percent compared with 5 percent) from 2000 to 2019 . . . , and they are expected to increase in the future.”

The report explains: “Farm labor costs are rising due to declining unauthorized migration, increasing state minimum wages, and some states removing overtime-pay exemptions for farm workers.”

The consequences? “In the short term, management changes include fewer repicks of fields and orchards, the introduction of mechanical aids such as robots that transport harvested produce from pickers to collection stations. In the long term, there is likely to be more labor-saving mechanization—with H-2A guest workers sometimes serving as a bridge to more mechanized production methods—and increased imports.”

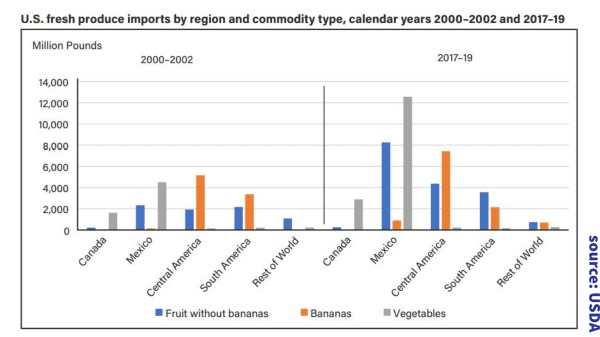

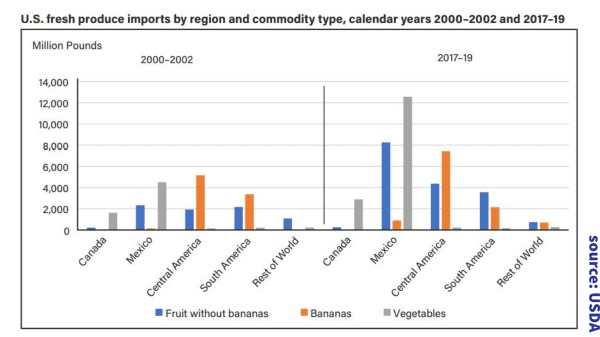

Another recent ERS report says, “In fiscal year (FY) 2021, the value of U.S. fruit and vegetable imports rose to a record level. That record is projected to rise another 9 percent in FY 2022 (October–September) to $42.6 billion. Import volumes are also expected to grow 3 percent in FY 2022 to 29.4 million metric tons. This would further extend the trend seen from FY 2000 to FY 2021, during which the volume of U.S. fruit and vegetable imports increased 124 percent while the inflation-adjusted value of those imports increased 208 percent.”

Meaning that the value of imported produce has increased even faster than the volume since the beginning of this century.

Meanwhile, some trends indicate that Mexican agriculture is moving away from row crops to crops such as berries.

The natural conclusion is that unless there is some reform in farm labor legislation that is more than window dressing—or mechanization of fruit and vegetable crops enjoys a sudden breakthrough—the United States and Mexico will grow toward a symbiotic relationship.

In this relationship, the U.S. would export more commodities that are well suited to mechanization, such as feed corn, south of the border, while Mexico would account for an increasing share of the fruits and vegetables consumed in the U.S.

Whether this trend would prove to be good, bad, or indifferent for you, of course, greatly depends on where and who you are in the produce industry.

It’s starting to look like a glitch in the Matrix.

Yet again, agricultural leaders are calling upon Congress to adopt some version of the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, which passed twice in the House of Representatives with bipartisan support, but which the Senate has so far failed to act on.

The law would go some way toward solving the acute crisis in agricultural labor.

I am not shrewd enough a politico to try to calculate the bill’s chances this time around, and I’m not a betting man, so I will avoid giving odds.

But a recently released report from USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS), entitled Adjusting to Higher Labor Costs in Selected U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Industries, by Linda Calvin, Philip Martin, and Skyler Simnitt, outlines the direction of current trends.

The report doesn’t contain any bombshells, but it does summarize the present situation concisely.

We learn, for example, that “farm labor wage rates—measured by real farm earnings—increased faster than nonfarm rates (16 percent compared with 5 percent) from 2000 to 2019 . . . , and they are expected to increase in the future.”

The report explains: “Farm labor costs are rising due to declining unauthorized migration, increasing state minimum wages, and some states removing overtime-pay exemptions for farm workers.”

The consequences? “In the short term, management changes include fewer repicks of fields and orchards, the introduction of mechanical aids such as robots that transport harvested produce from pickers to collection stations. In the long term, there is likely to be more labor-saving mechanization—with H-2A guest workers sometimes serving as a bridge to more mechanized production methods—and increased imports.”

Another recent ERS report says, “In fiscal year (FY) 2021, the value of U.S. fruit and vegetable imports rose to a record level. That record is projected to rise another 9 percent in FY 2022 (October–September) to $42.6 billion. Import volumes are also expected to grow 3 percent in FY 2022 to 29.4 million metric tons. This would further extend the trend seen from FY 2000 to FY 2021, during which the volume of U.S. fruit and vegetable imports increased 124 percent while the inflation-adjusted value of those imports increased 208 percent.”

Meaning that the value of imported produce has increased even faster than the volume since the beginning of this century.

Meanwhile, some trends indicate that Mexican agriculture is moving away from row crops to crops such as berries.

The natural conclusion is that unless there is some reform in farm labor legislation that is more than window dressing—or mechanization of fruit and vegetable crops enjoys a sudden breakthrough—the United States and Mexico will grow toward a symbiotic relationship.

In this relationship, the U.S. would export more commodities that are well suited to mechanization, such as feed corn, south of the border, while Mexico would account for an increasing share of the fruits and vegetables consumed in the U.S.

Whether this trend would prove to be good, bad, or indifferent for you, of course, greatly depends on where and who you are in the produce industry.

Richard Smoley, contributing editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 12 books.