Once in a while you will come across a funny word: “biodynamic.”

What does it mean?

It refers to a specific method of organic agriculture. All biodynamic agriculture is organic, though not all organic agriculture is biodynamic.

This approach to farming was inspired by the Austrian mystical philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925). In his voluminous works (his collected lectures alone fill 300 volumes), he addressed practically all areas of human concern.

One was education: Waldorf schools, a well-known form of alternative education, are directly based on Steiner’s thought. A wealthy German cigarette manufacturer wanted to set up a school for his workers’ children and asked Steiner for some guidelines, which blossomed into Waldorf education.

Similarly, biodynamic agriculture was inspired by a series of lectures to farmers that Steiner delivered in 1924.

“Each biodynamic farm or garden is an integrated, whole, living organism,” we read on the website of the Biodynamics Association. “This organism is made up of many interdependent elements: fields, forests, plants, animals, soils, compost, people, and the spirit of the place.”

“The spirit of the place”? Well, I told you that Steiner was a mystical philosopher.

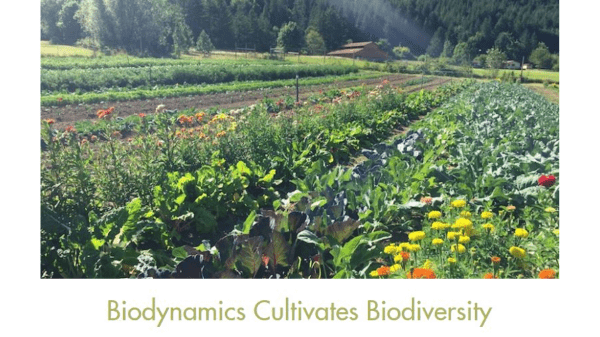

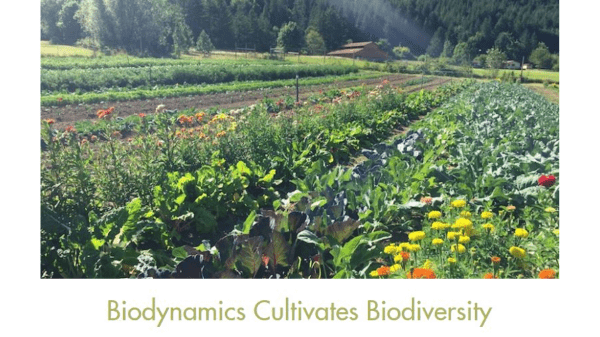

Whatever biodynamic farming may or may not be, it is not a monoculture.

“Biodynamic farms and gardens are inspired by the biodiversity of natural ecosystems and the uniqueness of each landscape,” says the Biodynamic Association’s website. “Annual and perennial vegetables, herbs, flowers, berries, fruits, nuts, grains, pasture, forage, native plants, and pollinator hedgerows can all contribute to plant diversity, amplifying the health and resilience of the farm organism.

“Diversity in domestic animals is also beneficial, as each animal species brings a different relationship to the land and unique quality of manure.”

This approach sees diversity as (among other things) a way of pest control. “When farms and gardens incorporate a robust diversity of plants and animals and create habitat for natural predators, pests and diseases have few places to thrive. When a disease or pest presents itself, it is often pointing to an imbalance in the farm organism.”

Some biodynamic methods hark back to ancient practices. “Biodynamic farmers and gardeners observe the rhythms and cycles of the earth, sun, moon, stars, and planets and seek to understand the subtle ways that the environment and wider cosmos influence the growth and development of plants and animals,” says the association’s website.

The knee-jerk response to this kind of approach is “it all sounds crazy.” Here as in many other cases, that isn’t enough reason to kick it aside.

Over 5,000 farms, encompassing more than 400,000 acres, are certified as biodynamic in 60 countries. Certification is governed by an organization called Demeter International.

One operation that has had success with biodynamic farming is the 900-acre Hawthorne Valley Farms in Ghent, in upstate New York. Its farm store attracts shoppers from as far away as New York City, which is about a three-hour drive away.

Another pocket of biodynamic agriculture is Burgundy in France, which has been producing some of the world’s greatest (and most expensive) wines since Roman times.

It’s hard to dismiss winegrowers here as a bunch of hippie nut jobs with dilated pupils and flowers in their hair.

Several produce companies have promoted their biodynamic offerings, including Awe Sum Organics BB #:157008 and Sun Belle Inc. BB #:126047

Biodynamic agriculture is a holistic agriculture in the deepest sense of the term: the entire operation is integrated according to its principles. As such, it’s likely to appeal to a limited number of growers, although they might want to poke into it to get some ideas, for example, on soil health and other matters of sustainability.

By the way—I have practically never seen biodynamic produce offered in a store. But when I did, it was extremely expensive.

Once in a while you will come across a funny word: “biodynamic.”

What does it mean?

It refers to a specific method of organic agriculture. All biodynamic agriculture is organic, though not all organic agriculture is biodynamic.

This approach to farming was inspired by the Austrian mystical philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925). In his voluminous works (his collected lectures alone fill 300 volumes), he addressed practically all areas of human concern.

One was education: Waldorf schools, a well-known form of alternative education, are directly based on Steiner’s thought. A wealthy German cigarette manufacturer wanted to set up a school for his workers’ children and asked Steiner for some guidelines, which blossomed into Waldorf education.

Similarly, biodynamic agriculture was inspired by a series of lectures to farmers that Steiner delivered in 1924.

“Each biodynamic farm or garden is an integrated, whole, living organism,” we read on the website of the Biodynamics Association. “This organism is made up of many interdependent elements: fields, forests, plants, animals, soils, compost, people, and the spirit of the place.”

“The spirit of the place”? Well, I told you that Steiner was a mystical philosopher.

Whatever biodynamic farming may or may not be, it is not a monoculture.

“Biodynamic farms and gardens are inspired by the biodiversity of natural ecosystems and the uniqueness of each landscape,” says the Biodynamic Association’s website. “Annual and perennial vegetables, herbs, flowers, berries, fruits, nuts, grains, pasture, forage, native plants, and pollinator hedgerows can all contribute to plant diversity, amplifying the health and resilience of the farm organism.

“Diversity in domestic animals is also beneficial, as each animal species brings a different relationship to the land and unique quality of manure.”

This approach sees diversity as (among other things) a way of pest control. “When farms and gardens incorporate a robust diversity of plants and animals and create habitat for natural predators, pests and diseases have few places to thrive. When a disease or pest presents itself, it is often pointing to an imbalance in the farm organism.”

Some biodynamic methods hark back to ancient practices. “Biodynamic farmers and gardeners observe the rhythms and cycles of the earth, sun, moon, stars, and planets and seek to understand the subtle ways that the environment and wider cosmos influence the growth and development of plants and animals,” says the association’s website.

The knee-jerk response to this kind of approach is “it all sounds crazy.” Here as in many other cases, that isn’t enough reason to kick it aside.

Over 5,000 farms, encompassing more than 400,000 acres, are certified as biodynamic in 60 countries. Certification is governed by an organization called Demeter International.

One operation that has had success with biodynamic farming is the 900-acre Hawthorne Valley Farms in Ghent, in upstate New York. Its farm store attracts shoppers from as far away as New York City, which is about a three-hour drive away.

Another pocket of biodynamic agriculture is Burgundy in France, which has been producing some of the world’s greatest (and most expensive) wines since Roman times.

It’s hard to dismiss winegrowers here as a bunch of hippie nut jobs with dilated pupils and flowers in their hair.

Several produce companies have promoted their biodynamic offerings, including Awe Sum Organics BB #:157008 and Sun Belle Inc. BB #:126047

Biodynamic agriculture is a holistic agriculture in the deepest sense of the term: the entire operation is integrated according to its principles. As such, it’s likely to appeal to a limited number of growers, although they might want to poke into it to get some ideas, for example, on soil health and other matters of sustainability.

By the way—I have practically never seen biodynamic produce offered in a store. But when I did, it was extremely expensive.

Richard Smoley, contributing editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 12 books.