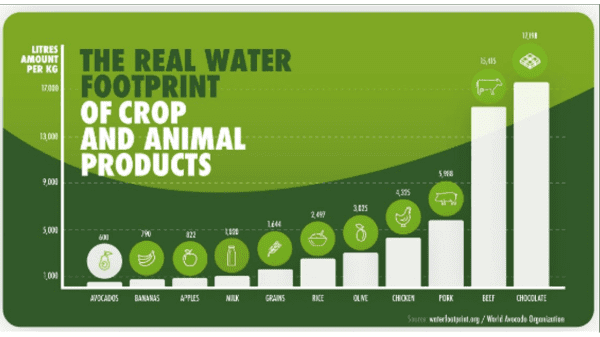

Chart courtesy World Avocado Organization

“Give peas a chance,” urges the British newspaper The Guardian.

They mean instead of avocados. An article dated November 1 has the headline.

Irish author and chef J.P. McMahon has even called them “the blood diamonds of fruit.”

Objections to the admittedly delicious item include alleged unsustainability and exploitation. “Avocados show how wrong our food system is,” says McMahon. “At the moment, most of the world’s avocados come from Mexico. There are a lot of issues with cartel involvement in the ownership and also the pressure placed on avocado farmers.”

A spokesperson for Avocados from Mexico (AFM) counters that cartels do not control the avocado industry. “In Mexico, there are approximately 29,000 avocado growers and 65 packers, and the vast majority are cultivating in less than 5 acres on family-owned and operated farms (67% of the orchards occupy less than 25 acres each, and another 25% occupy 25-75 acres).”

The Guardian article said that avocados “have an enormous carbon footprint for a fruit, require up to 320 litres of water each to grow,” and are becoming unaffordable to people who live in avocado growing areas. (A November 8 correction to the article clarified that “a reference in the text to one avocado needing 320 litres of water to grow is an extreme and specific example, but not typical.”)

Water supplies are indeed critical concerns in the avocado growing areas of California and Chile. But the AFM spokesperson replies, “Because . . . the majority of avocados come from Mexico, it is misleading to readers to state that water use is a serious issue with regard to avocado production.” She says that 85 percent of Michoacán avocados rely on rainfall for water, citing information from the Avocado Institute of Mexico (https://avocadoinstitute.org/the-green-agenda-a-cycle-of-sustainability/).

Colombian avocados, an increasingly important factor in the industry, also pose minimal threats to the water supply. “We’re in the tropics,” says Mauricio Lopez, manager for sales for Bogotá-based Green Superfood, “so in Colombia we don’t have problems with water as a natural resource.” The region has rainfall of 2,000 millimeters per year (79 inches), so “you don’t need to take much water from other sources.”

Some trendy British chefs are fashioning ersatz guacamole. Thomasina Myers, cofounder of a Mexican food chain called Wahaca, has concocted a “Wahacamole” out of fava beans, lime, chili, and coriander (probably coriander leaf, i.e., cilantro, to judge from the photo). Other surrogate vegetables include British peas and zucchini (or courgettes, as they call them over there).

The Guardian article irked Xavier Equihua, president of the World Avocado Organization, who, in a letter to the editor, criticized “the greenwashing efforts of some restaurateurs who claim environmental responsibility by removing the avocado which takes on average 600 liters to produce a kilo (or 5 to 6 medium size avocados). Meanwhile the imitation guacamole is made from fava beans, which require roughly 5000 liters to produce a single kilo…Many of these restaurateurs are keeping dozens of ingredients with a far greater environmental footprint on their menus.”

The British foodies are not so much singling out the avocado as criticizing the food production system as a whole. “I think if you take any product to an industrial level, you put pressure on the environment,” McMahon told BBC Scotland.

Possibly—but then what is left for him to serve?

Another dynamic: trendiness is a moving target. Something becomes hip for whatever reason (avocado toast, Civil War-era beards, baseball caps worn backward), but the moment it does, self-proclaimed avant-gardistes sneer at it in order to keep ahead of the crowd.

Personally, I would be delighted to try any of the ersatz guacamoles that creative chefs might devise.

I doubt, however, that their concerns will percolate down to the public, at least in this country. We can reliably predict that sweatshirt-clad Americans will sit down to the next Super Bowl while munching on guacamole made from the real thing.

This is a version of a previous article, updated to include additional information on water use and ownership of avocado production in Mexico.

“Give peas a chance,” urges the British newspaper The Guardian.

They mean instead of avocados. An article dated November 1 has the headline.

Irish author and chef J.P. McMahon has even called them “the blood diamonds of fruit.”

Objections to the admittedly delicious item include alleged unsustainability and exploitation. “Avocados show how wrong our food system is,” says McMahon. “At the moment, most of the world’s avocados come from Mexico. There are a lot of issues with cartel involvement in the ownership and also the pressure placed on avocado farmers.”

A spokesperson for Avocados from Mexico (AFM) counters that cartels do not control the avocado industry. “In Mexico, there are approximately 29,000 avocado growers and 65 packers, and the vast majority are cultivating in less than 5 acres on family-owned and operated farms (67% of the orchards occupy less than 25 acres each, and another 25% occupy 25-75 acres).”

The Guardian article said that avocados “have an enormous carbon footprint for a fruit, require up to 320 litres of water each to grow,” and are becoming unaffordable to people who live in avocado growing areas. (A November 8 correction to the article clarified that “a reference in the text to one avocado needing 320 litres of water to grow is an extreme and specific example, but not typical.”)

Water supplies are indeed critical concerns in the avocado growing areas of California and Chile. But the AFM spokesperson replies, “Because . . . the majority of avocados come from Mexico, it is misleading to readers to state that water use is a serious issue with regard to avocado production.” She says that 85 percent of Michoacán avocados rely on rainfall for water, citing information from the Avocado Institute of Mexico (https://avocadoinstitute.org/the-green-agenda-a-cycle-of-sustainability/).

Colombian avocados, an increasingly important factor in the industry, also pose minimal threats to the water supply. “We’re in the tropics,” says Mauricio Lopez, manager for sales for Bogotá-based Green Superfood, “so in Colombia we don’t have problems with water as a natural resource.” The region has rainfall of 2,000 millimeters per year (79 inches), so “you don’t need to take much water from other sources.”

Some trendy British chefs are fashioning ersatz guacamole. Thomasina Myers, cofounder of a Mexican food chain called Wahaca, has concocted a “Wahacamole” out of fava beans, lime, chili, and coriander (probably coriander leaf, i.e., cilantro, to judge from the photo). Other surrogate vegetables include British peas and zucchini (or courgettes, as they call them over there).

The Guardian article irked Xavier Equihua, president of the World Avocado Organization, who, in a letter to the editor, criticized “the greenwashing efforts of some restaurateurs who claim environmental responsibility by removing the avocado which takes on average 600 liters to produce a kilo (or 5 to 6 medium size avocados). Meanwhile the imitation guacamole is made from fava beans, which require roughly 5000 liters to produce a single kilo…Many of these restaurateurs are keeping dozens of ingredients with a far greater environmental footprint on their menus.”

The British foodies are not so much singling out the avocado as criticizing the food production system as a whole. “I think if you take any product to an industrial level, you put pressure on the environment,” McMahon told BBC Scotland.

Possibly—but then what is left for him to serve?

Another dynamic: trendiness is a moving target. Something becomes hip for whatever reason (avocado toast, Civil War-era beards, baseball caps worn backward), but the moment it does, self-proclaimed avant-gardistes sneer at it in order to keep ahead of the crowd.

Personally, I would be delighted to try any of the ersatz guacamoles that creative chefs might devise.

I doubt, however, that their concerns will percolate down to the public, at least in this country. We can reliably predict that sweatshirt-clad Americans will sit down to the next Super Bowl while munching on guacamole made from the real thing.

This is a version of a previous article, updated to include additional information on water use and ownership of avocado production in Mexico.

Richard Smoley, contributing editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 12 books.