Economic forecasting is a treacherous art, and one that would seem to be doomed to failure. It can only predict on the basis of current trends, but of course current trends don’t continue.

There are constant surprises and dislocations—as anyone knows who has lived through 2020.

Nevertheless, the exercise must have value because experts keep doing it. This month USDA released a report entitled Agricultural Production to 2030.

It contains this necessary disclaimer: “The report assumes that there are no domestic or external shocks during the projection period that would affect global agricultural supply and demand. Changes in any of these assumptions can significantly affect the projections, and actual conditions that emerge will alter the outcomes.”

And we can rest assured that there will indeed be domestic and external shocks.

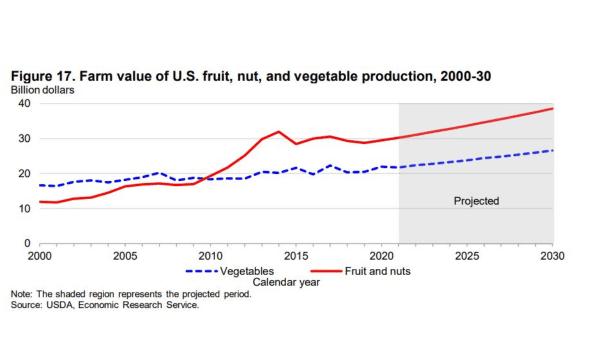

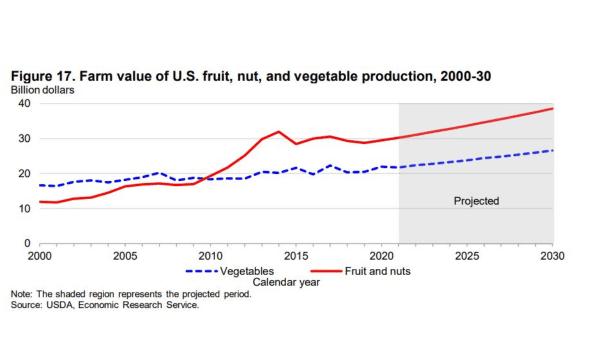

Most of the report deals with the major row crops and meat, but there is a small section on fruit and vegetable projections. By 2030, it says, the total combined farm value of fruit, tree nuts, vegetable, and pulse crop production will rise from 2020’s $51.4 billion to $65.1 billion.

“Combined production of fruit, tree nuts, vegetable, and pulses grow slightly over the next decade, reaching 189 billion pounds by 2030, up from 186 billion in 2020.”

Fruit will constitute nearly 27 percent of total output and 38 percent of total value; tree nuts approximately 4.5 percent of output and 21 percent of value; and vegetables and pulses 68.5 percent of output and 41 percent of value.

The report sees vegetable and pulse production as growing “only slightly” for the rest of the decade. One reason is “rising import competition.”

But the report goes on to say that there are “technical measuring issues” as a result of “the rapid growth of the protected culture subsector (mostly greenhouses and urban vertical farms) which is slowly replacing field-grown production for several major vegetables. . . . With some exceptions, this sector is not well represented in traditional USDA data collection programs which have recorded declining field-grown area and production for some crops.”

Which, being translated, means that USDA hasn’t been in the habit of collecting much data on greenhouse crops. Which in turn means that USDA may be underestimating growth in vegetable production.

Fresh-market vegetables are expected to remain at about 31 percent of vegetable production, because imports will “largely fill stronger demand through 2030.” Nevertheless, the value of fresh-market production will rise by one third, “buoyed in-part by increasing production of higher-priced organic vegetables.”

Potato production will rise slightly, as a decline in acreage will be “more than offset by a gain in yields.” Furthermore, the potato industry “faces increasing competition from imported products, especially among frozen products.” Potato prices and crop values will rise modestly during this time, according to the report.

U.S. fruit and tree nut production (in pounds) is projected to grow 0.35 percent annually during the 2020s, “reaching roughly 59 billion pounds by 2030.” U.S. citrus output, on the other hand, is expected to decline 0.65 percent annually, although higher prices will raise the farm value.

The farm value of fruit and tree nuts will grow 2.7 annually over the production period, with tree nuts growing at 3 percent, citrus at 2.9 percent, and noncitrus at 2.5 percent.

Total agricultural imports are expected to grow from 2020’s $133.2 billion to $174.5 billion in 2030.

“The United States largely imports products that are out of season or not widely grown domestically,” the report explains. “Many imported products are differentiated or high-value products for which demand is less sensitive to price and currency fluctuations. The highest growth commodity sector by value is expected to be horticultural products, which are projected to expand about 5 percent per year, largely driven by fresh fruit and vegetable purchases.”

U.S. fresh fruit and vegetable exports are expected to rise from $7 billion in 2020 to $9.6 billion in 2030. Fresh fruit and vegetable imports will increase more sharply, from $23.9 billion in 2020 to $36.6 billion in 2030, “as domestic preferences for a diverse array of agricultural goods continue to exceed domestic production.”

We can be confident that this “diverse array” will be heavily represented by produce crops.

Economic forecasting is a treacherous art, and one that would seem to be doomed to failure. It can only predict on the basis of current trends, but of course current trends don’t continue.

There are constant surprises and dislocations—as anyone knows who has lived through 2020.

Nevertheless, the exercise must have value because experts keep doing it. This month USDA released a report entitled Agricultural Production to 2030.

It contains this necessary disclaimer: “The report assumes that there are no domestic or external shocks during the projection period that would affect global agricultural supply and demand. Changes in any of these assumptions can significantly affect the projections, and actual conditions that emerge will alter the outcomes.”

And we can rest assured that there will indeed be domestic and external shocks.

Most of the report deals with the major row crops and meat, but there is a small section on fruit and vegetable projections. By 2030, it says, the total combined farm value of fruit, tree nuts, vegetable, and pulse crop production will rise from 2020’s $51.4 billion to $65.1 billion.

“Combined production of fruit, tree nuts, vegetable, and pulses grow slightly over the next decade, reaching 189 billion pounds by 2030, up from 186 billion in 2020.”

Fruit will constitute nearly 27 percent of total output and 38 percent of total value; tree nuts approximately 4.5 percent of output and 21 percent of value; and vegetables and pulses 68.5 percent of output and 41 percent of value.

The report sees vegetable and pulse production as growing “only slightly” for the rest of the decade. One reason is “rising import competition.”

But the report goes on to say that there are “technical measuring issues” as a result of “the rapid growth of the protected culture subsector (mostly greenhouses and urban vertical farms) which is slowly replacing field-grown production for several major vegetables. . . . With some exceptions, this sector is not well represented in traditional USDA data collection programs which have recorded declining field-grown area and production for some crops.”

Which, being translated, means that USDA hasn’t been in the habit of collecting much data on greenhouse crops. Which in turn means that USDA may be underestimating growth in vegetable production.

Fresh-market vegetables are expected to remain at about 31 percent of vegetable production, because imports will “largely fill stronger demand through 2030.” Nevertheless, the value of fresh-market production will rise by one third, “buoyed in-part by increasing production of higher-priced organic vegetables.”

Potato production will rise slightly, as a decline in acreage will be “more than offset by a gain in yields.” Furthermore, the potato industry “faces increasing competition from imported products, especially among frozen products.” Potato prices and crop values will rise modestly during this time, according to the report.

U.S. fruit and tree nut production (in pounds) is projected to grow 0.35 percent annually during the 2020s, “reaching roughly 59 billion pounds by 2030.” U.S. citrus output, on the other hand, is expected to decline 0.65 percent annually, although higher prices will raise the farm value.

The farm value of fruit and tree nuts will grow 2.7 annually over the production period, with tree nuts growing at 3 percent, citrus at 2.9 percent, and noncitrus at 2.5 percent.

Total agricultural imports are expected to grow from 2020’s $133.2 billion to $174.5 billion in 2030.

“The United States largely imports products that are out of season or not widely grown domestically,” the report explains. “Many imported products are differentiated or high-value products for which demand is less sensitive to price and currency fluctuations. The highest growth commodity sector by value is expected to be horticultural products, which are projected to expand about 5 percent per year, largely driven by fresh fruit and vegetable purchases.”

U.S. fresh fruit and vegetable exports are expected to rise from $7 billion in 2020 to $9.6 billion in 2030. Fresh fruit and vegetable imports will increase more sharply, from $23.9 billion in 2020 to $36.6 billion in 2030, “as domestic preferences for a diverse array of agricultural goods continue to exceed domestic production.”

We can be confident that this “diverse array” will be heavily represented by produce crops.

Richard Smoley, an editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 11 books.