What’s the outlook on farm labor? In a recent interview, Philip L. Martin, a professor at the University of California at Davis and one of the nation’s leading experts, made three major points.

The first one: at the end of 2020, it’s clear that “ag survived Covid-19,” says Martin. “By and large shipments were very similar in 2020 and 2019. That should mean that employment was similar,” although “employment data are lagging. Employers don’t get penalized for not sending in data.”

Nevertheless, ag didn’t emerge unscathed. Martin goes on to point out that “Covid involved a cost-price squeeze; costs for growers went up,” for example in “shifting from foodservice to retail. Costs went up; prices did not necessarily rise.”

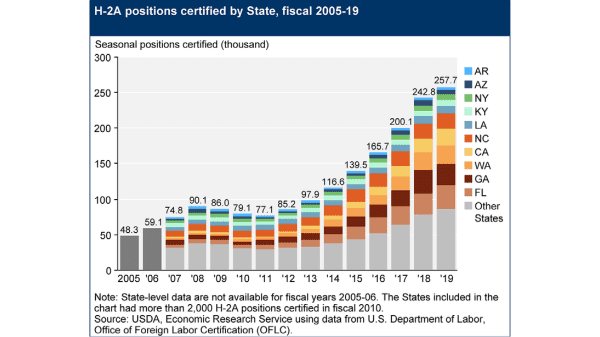

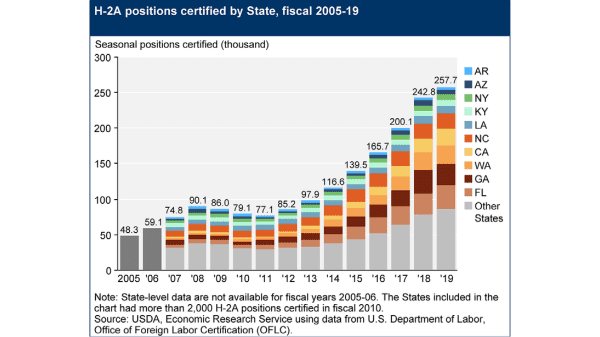

In addition, the virus accelerated trends “that were going to be happening anyway,” says Martin. This included a continued growth in the H-2A guest worker program.

Although the programs require employers to recruit domestic employees first, “DOL [the Department of Labor] has been certifying 95-100 percent of requests” for H-2A employees, which, he says, “signaled that we’re not going to get a lot of U.S. farmworkers.”

Martin also sees a continued push toward mechanization. Certainly, there have been efforts to integrate robotics, for example, into produce harvesting. A company called Abundant Robotics has released a harvester for fresh tomatoes, called the Automato, which, it claims, can pick 12,000 tomatoes a day.

Although it is slower than a human worker, it can work up to 16 hours a day. The company has also developed a preproduction prototype for an apple harvester.

But these developments are still years away from becoming standard features in fields and orchards. Martin believes that there has been “overpromise on the technology front.”

The third trend Martin sees is an increase in imports. This is more than a matter of lower labor costs in foreign countries.

New produce varieties are being developed that do better in warm, humid climates. He cites the Mexican blueberry industry as an example, which would not exist without varieties that can thrive in the warm, humid climate: until recently, blueberries were a crop from cooler northern regions.

American blueberry growers have taken notice and recently formed the American Blueberry Growers Alliance, whose website says, “Foreign exporters are targeting the U.S. blueberry market. A dramatic impact on the U.S. harvest period and extremely low import pricing has had a devastating impact on the domestic blueberry industry.”

Other factors continue to press U.S. agriculture. In strawberries, for example, Martin points to the loss of methyl bromide for preplant fumigation in 2016, but this is not the only problem here.

In a 2019 interview, Julie Guthman, author of Wilted: Pathogens, Chemicals, and the Fragile Future of the Strawberry Industry, observed, “A lot of [strawberry] growers have gone out of business, not just because of the chemicals but because of this perfect storm of events. Our crazy border policy has driven labor costs up. Land prices have gone way up. The best land is near the coast. If you go inland you have more disease problems, but real estate prices along the California coast keep going up. So there has been consolidation among the growers, and the shippers.”

Martin discussed the three points above in more detail at a presentation at the 2020 conference of the National Council of Agricultural Employers.

For a download of the presentation, click here.

What’s the outlook on farm labor? In a recent interview, Philip L. Martin, a professor at the University of California at Davis and one of the nation’s leading experts, made three major points.

The first one: at the end of 2020, it’s clear that “ag survived Covid-19,” says Martin. “By and large shipments were very similar in 2020 and 2019. That should mean that employment was similar,” although “employment data are lagging. Employers don’t get penalized for not sending in data.”

Nevertheless, ag didn’t emerge unscathed. Martin goes on to point out that “Covid involved a cost-price squeeze; costs for growers went up,” for example in “shifting from foodservice to retail. Costs went up; prices did not necessarily rise.”

In addition, the virus accelerated trends “that were going to be happening anyway,” says Martin. This included a continued growth in the H-2A guest worker program.

Although the programs require employers to recruit domestic employees first, “DOL [the Department of Labor] has been certifying 95-100 percent of requests” for H-2A employees, which, he says, “signaled that we’re not going to get a lot of U.S. farmworkers.”

Martin also sees a continued push toward mechanization. Certainly, there have been efforts to integrate robotics, for example, into produce harvesting. A company called Abundant Robotics has released a harvester for fresh tomatoes, called the Automato, which, it claims, can pick 12,000 tomatoes a day.

Although it is slower than a human worker, it can work up to 16 hours a day. The company has also developed a preproduction prototype for an apple harvester.

But these developments are still years away from becoming standard features in fields and orchards. Martin believes that there has been “overpromise on the technology front.”

The third trend Martin sees is an increase in imports. This is more than a matter of lower labor costs in foreign countries.

New produce varieties are being developed that do better in warm, humid climates. He cites the Mexican blueberry industry as an example, which would not exist without varieties that can thrive in the warm, humid climate: until recently, blueberries were a crop from cooler northern regions.

American blueberry growers have taken notice and recently formed the American Blueberry Growers Alliance, whose website says, “Foreign exporters are targeting the U.S. blueberry market. A dramatic impact on the U.S. harvest period and extremely low import pricing has had a devastating impact on the domestic blueberry industry.”

Other factors continue to press U.S. agriculture. In strawberries, for example, Martin points to the loss of methyl bromide for preplant fumigation in 2016, but this is not the only problem here.

In a 2019 interview, Julie Guthman, author of Wilted: Pathogens, Chemicals, and the Fragile Future of the Strawberry Industry, observed, “A lot of [strawberry] growers have gone out of business, not just because of the chemicals but because of this perfect storm of events. Our crazy border policy has driven labor costs up. Land prices have gone way up. The best land is near the coast. If you go inland you have more disease problems, but real estate prices along the California coast keep going up. So there has been consolidation among the growers, and the shippers.”

Martin discussed the three points above in more detail at a presentation at the 2020 conference of the National Council of Agricultural Employers.

For a download of the presentation, click here.

Richard Smoley, an editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 11 books.