The FDA and CDC are investigating three separate multi-state E. coli outbreaks, but they haven’t linked them to any specific foods.

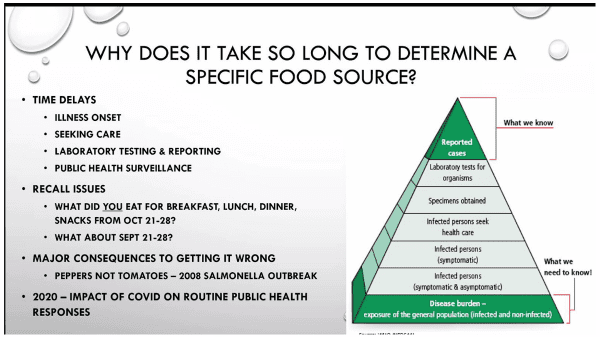

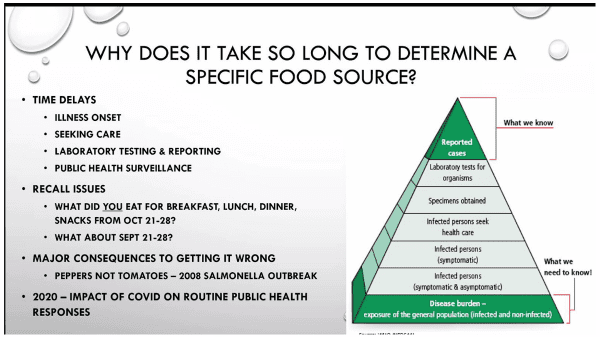

Kristen Pogreba-Brown, assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Arizona, said people get frustrated at why these investigations take so long, but there are many reasons.

“Right now, most of CDC has been deployed to work on COVID,” she said on a Produce Marketing Association BB #:153708 webinar November 18.

Other challenges include the difficulty of having sick people get tested, the lack of consistency in investigations among state health groups, and the high stakes of outbreaks.

“We can’t know unless a consumer gets tested,” she said.

One problem is that investigators often ask sick people to recall what they ate each day from a period that’s three to four weeks ago.

And then, if they find an illness cluster, they’ll ask that same consumer to recall what they ate every day a month before that, Pogreba-Brown said.

The CDC runs the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, or FoodNet, which helps with consistency in multi-state investigations, but not every state uses it.

“There’s no one systemic way to collect data,” she said.

Another issue is that investigators often only have a handful of linked cases.

“It’s dangerous to make broad assumptions based on a small amount of data,” Pogreba-Brown said, noting that in 2008, federal health authorities named tomatoes as the cause of a widespread outbreak, when it later turned out to be peppers as the cause.

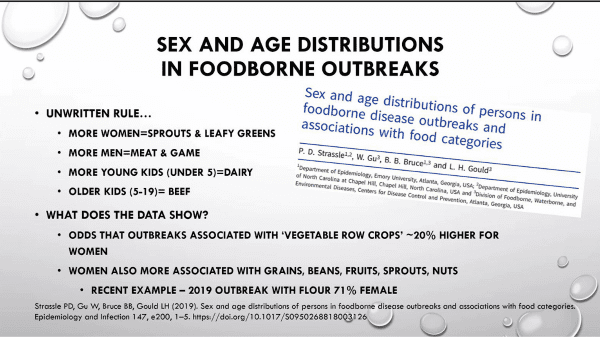

Interestingly, she said there are some assumptions that investigators can make early in the process of an outbreak based on demographics of those who are ill.

For example, one of these “unwritten rules” notes that outbreaks associated with vegetable row crops tend to affect women 20 percent more than men. Likewise, when it’s a higher percentage of men who are sick, the food involved is often meat and game, and when it’s children, it’s often dairy products.

It’s not just gender stereotypes, “the data shows these are correct,” she said.

The FDA and CDC are investigating three separate multi-state E. coli outbreaks, but they haven’t linked them to any specific foods.

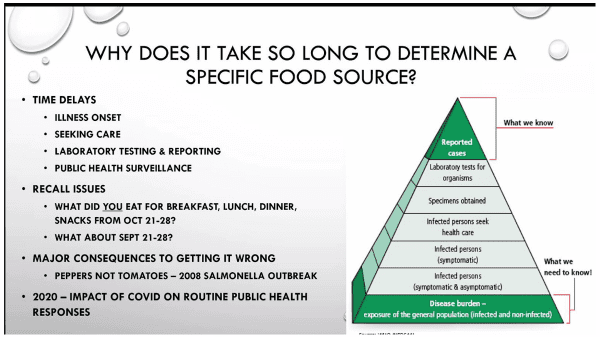

Kristen Pogreba-Brown, assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Arizona, said people get frustrated at why these investigations take so long, but there are many reasons.

“Right now, most of CDC has been deployed to work on COVID,” she said on a Produce Marketing Association BB #:153708 webinar November 18.

Other challenges include the difficulty of having sick people get tested, the lack of consistency in investigations among state health groups, and the high stakes of outbreaks.

“We can’t know unless a consumer gets tested,” she said.

One problem is that investigators often ask sick people to recall what they ate each day from a period that’s three to four weeks ago.

And then, if they find an illness cluster, they’ll ask that same consumer to recall what they ate every day a month before that, Pogreba-Brown said.

The CDC runs the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, or FoodNet, which helps with consistency in multi-state investigations, but not every state uses it.

“There’s no one systemic way to collect data,” she said.

Another issue is that investigators often only have a handful of linked cases.

“It’s dangerous to make broad assumptions based on a small amount of data,” Pogreba-Brown said, noting that in 2008, federal health authorities named tomatoes as the cause of a widespread outbreak, when it later turned out to be peppers as the cause.

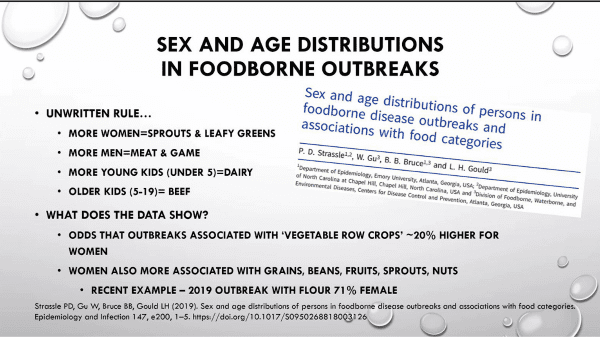

Interestingly, she said there are some assumptions that investigators can make early in the process of an outbreak based on demographics of those who are ill.

For example, one of these “unwritten rules” notes that outbreaks associated with vegetable row crops tend to affect women 20 percent more than men. Likewise, when it’s a higher percentage of men who are sick, the food involved is often meat and game, and when it’s children, it’s often dairy products.

It’s not just gender stereotypes, “the data shows these are correct,” she said.

Greg Johnson is Director of Media Development for Blue Book Services