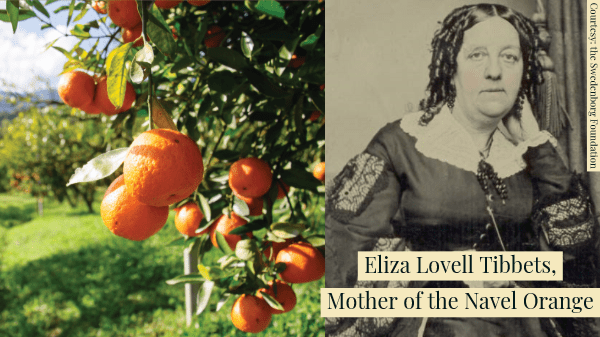

Every navel orange eaten, shipped, or sold owes its origin to two trees planted in Riverside, CA in 1873. The woman who planted them was both exceptional and typical of her time—the idealistic, inspirational, yet highly pragmatic America of the mid-nineteenth century.

The woman was Eliza Lovell Tibbets (1823-98), a Cincinnati native whose life story included three marriages, a prominent role in suffragism and spiritualism, and an abortive attempt at a racially integrated intentional community.

Eliza and her equally idealistic third husband, Luther Tibbets, met in New York City when both were married to other people, whom they divorced to marry each other in 1865. America in that age was the seedbed of many utopian communities, meant to create more harmonious lives for their residents.

The Tibbets started theirs in Fredericksburg, VA, much of which had been destroyed in two Civil War battles. The couple’s advocacy of racial equality won them the hatred of the local white population, which signaled its hostility through threatening letters from the Ku Klux Klan (“It is not our desire to shed blood, and it is only done in extreme cases when assassination cannot be avoided”).

Taking the hint, the Tibbets moved to Washington, DC in 1868, where Eliza made the acquaintance of William Saunders, head of the U.S. Agricultural Department’s division of experimental gardens and grounds. Saunders would later send Eliza the two cuttings that would launch the navel orange industry.

In 1870, the couple learned of a utopian community being founded in California by a judge named John Wesley North. Like the Tibbets, North had encountered difficulties because of his advocacy of racial equality: he had been driven out of Knoxville, TN for interfering with the lynching of a black man. In search of land that could be used for horticulture, North found an ideal location fifty-five miles east of Los Angeles, and the town of Riverside was incorporated in 1870.

Luther, along with Jimmy Summons, Eliza’s son from her first marriage, went ahead to build a house before having the rest of the family come.

In the meantime, Saunders, back in Washington, received some clippings of an orange tree from Bahia, Brazil. Its oranges were distinctive not only for their sweetness, but because they had a kind of navel on the blossom end. Furthermore, they were seedless and could only be propagated by cuttings.

Eliza, by then in Riverside, wrote to Saunders requesting some cuttings, which he sent. She planted them in the front yard of her house in 1873, launching a stupendous industry.

The Tibbets lauded the fruit from their two trees. They nearly killed them by taking so many cuttings, but the industry burgeoned over the next decades. In April 1902, The New York Times reported that “Riverside County sends some 8,000 carloads of seedless oranges to market annually, and they are worth to the growers about $3,000,000.”

The Tibbets themselves profited by selling clippings, from which, according to one source, they made $20,000 ($528,000 in 2019 dollars) in a single year in the early 1880s.

Luther was no businessman—he seemed to live for filing lawsuits—and the Tibbets’ prosperity was short-lived. In 1897 the mortgage on their house and property was foreclosed. By then, Eliza was spending most of her time on the California coast (the dry, dusty Riverside climate did not suit her bronchitis), where she died in 1898.

Luther fought the foreclosure, but in vain, and in 1902 The New York Times reported, “Luther C. Tibbets, who planted the original [navel orange] tree, is a homeless, white-haired public charge in Riverside County.” He died penniless in July 1902 and was buried next to his wife in the Riverside cemetery.

But the two trees continued to thrive. One survived until 1922, when it succumbed to gummosis, or root rot. The other tree still lives and is now located at 4550 Arlington Avenue in Riverside—a California state landmark.

Like many citrus trees in Southern California (and elsewhere), it is currently threatened by HLB disease. Two trees planted next to it were removed in April 2019 as a precaution.

The story of Eliza and Luther Tibbets is summed up well in the title of a book by Eliza’s great-great-granddaughter Patricia Ortlieb and coauthor Peter Economy—Creating an Orange Utopia: Eliza Lovell Tibbets and the Birth of the California Citrus Industry.

This is multi-part feature on the U.S. citrus industry adapted from the January/February 2020 issue of Produce Blueprints.

Every navel orange eaten, shipped, or sold owes its origin to two trees planted in Riverside, CA in 1873. The woman who planted them was both exceptional and typical of her time—the idealistic, inspirational, yet highly pragmatic America of the mid-nineteenth century.

The woman was Eliza Lovell Tibbets (1823-98), a Cincinnati native whose life story included three marriages, a prominent role in suffragism and spiritualism, and an abortive attempt at a racially integrated intentional community.

Eliza and her equally idealistic third husband, Luther Tibbets, met in New York City when both were married to other people, whom they divorced to marry each other in 1865. America in that age was the seedbed of many utopian communities, meant to create more harmonious lives for their residents.

The Tibbets started theirs in Fredericksburg, VA, much of which had been destroyed in two Civil War battles. The couple’s advocacy of racial equality won them the hatred of the local white population, which signaled its hostility through threatening letters from the Ku Klux Klan (“It is not our desire to shed blood, and it is only done in extreme cases when assassination cannot be avoided”).

Taking the hint, the Tibbets moved to Washington, DC in 1868, where Eliza made the acquaintance of William Saunders, head of the U.S. Agricultural Department’s division of experimental gardens and grounds. Saunders would later send Eliza the two cuttings that would launch the navel orange industry.

In 1870, the couple learned of a utopian community being founded in California by a judge named John Wesley North. Like the Tibbets, North had encountered difficulties because of his advocacy of racial equality: he had been driven out of Knoxville, TN for interfering with the lynching of a black man. In search of land that could be used for horticulture, North found an ideal location fifty-five miles east of Los Angeles, and the town of Riverside was incorporated in 1870.

Luther, along with Jimmy Summons, Eliza’s son from her first marriage, went ahead to build a house before having the rest of the family come.

In the meantime, Saunders, back in Washington, received some clippings of an orange tree from Bahia, Brazil. Its oranges were distinctive not only for their sweetness, but because they had a kind of navel on the blossom end. Furthermore, they were seedless and could only be propagated by cuttings.

Eliza, by then in Riverside, wrote to Saunders requesting some cuttings, which he sent. She planted them in the front yard of her house in 1873, launching a stupendous industry.

The Tibbets lauded the fruit from their two trees. They nearly killed them by taking so many cuttings, but the industry burgeoned over the next decades. In April 1902, The New York Times reported that “Riverside County sends some 8,000 carloads of seedless oranges to market annually, and they are worth to the growers about $3,000,000.”

The Tibbets themselves profited by selling clippings, from which, according to one source, they made $20,000 ($528,000 in 2019 dollars) in a single year in the early 1880s.

Luther was no businessman—he seemed to live for filing lawsuits—and the Tibbets’ prosperity was short-lived. In 1897 the mortgage on their house and property was foreclosed. By then, Eliza was spending most of her time on the California coast (the dry, dusty Riverside climate did not suit her bronchitis), where she died in 1898.

Luther fought the foreclosure, but in vain, and in 1902 The New York Times reported, “Luther C. Tibbets, who planted the original [navel orange] tree, is a homeless, white-haired public charge in Riverside County.” He died penniless in July 1902 and was buried next to his wife in the Riverside cemetery.

But the two trees continued to thrive. One survived until 1922, when it succumbed to gummosis, or root rot. The other tree still lives and is now located at 4550 Arlington Avenue in Riverside—a California state landmark.

Like many citrus trees in Southern California (and elsewhere), it is currently threatened by HLB disease. Two trees planted next to it were removed in April 2019 as a precaution.

The story of Eliza and Luther Tibbets is summed up well in the title of a book by Eliza’s great-great-granddaughter Patricia Ortlieb and coauthor Peter Economy—Creating an Orange Utopia: Eliza Lovell Tibbets and the Birth of the California Citrus Industry.

This is multi-part feature on the U.S. citrus industry adapted from the January/February 2020 issue of Produce Blueprints.

Richard Smoley, editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published eleven books.