How & Why

(Information & Insight)

So we’ve established that credit applications are a tool for gathering information, but they serve a number of other

Giving Credit Where Credit Is Due

Your credit application is key

The effective use of credit applications is a foundational element for success within the produce industry, and pretty much any other business sector. Here are the basics on how to create a credit application, and make it work for you to strengthen your business.

What

(Purpose & Plan)

Credit is a fact of life; getting it is key to obtaining goods and giving it can make or break a company. Credit applications are an essential tool finance managers can use to get to know their customers and, more importantly, forge a mutually beneficial business relationship. It can also help calculate the odds of a new business partner paying its bills on time.

A properly completed credit application is comprised of several critical components, in addition to providing the necessary information to determine if credit is warranted, at what amount, and the risks involved. Applications also give finance managers the necessary permission to contact references, whether bank or trade, and spell out terms, which applicants must acknowledge and accept. When used in conjunction with other sources of information, credit managers can gain valuable insight into a company’s financial health.

“You can’t pay bills with forklifts, buildings, or land; you have to pay them with cash,” comments Charles Brown, director of credit for Hapco Farms in Riverhead, NY. “So liquidity is everything. That’s what we’re always trying to assess.”

Who & When

(Authority & Authorization)

Del Campo Supreme in Nogales, AZ expects everyone who wants to do business with the company to fill out a credit application. “I require a credit application for all our customers who are not set up in our system,” says Cathy Jimenez, credit manager.

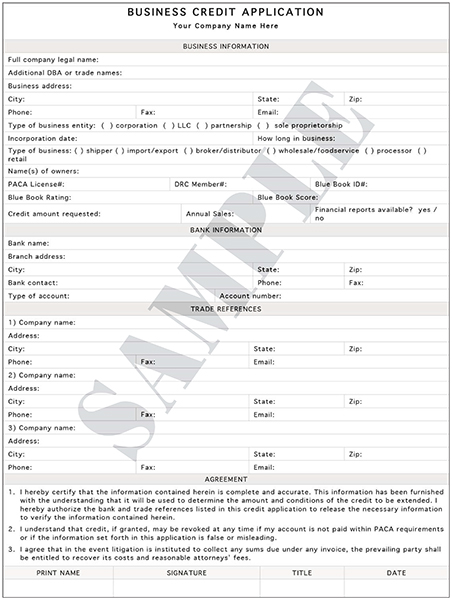

Aside from company name and contact information, most credit applications (to view a sample, see page 30) ask for incorporation date and length of time in business, legal entity type (corporation, sole proprietor, partnership, etc.), bank information, and the names of references from multiple trading partners.

All information, however, must be verified, including whether the person submitting the application is authorized to do so. Del Campo Supreme requires all credit applications to be signed by a corporate officer (a chief executive officer is ideal—forms signed by lower level managers or sales staff are generally not accepted).

Brown agrees it’s critical to know if the submitter is authorized to seek credit, and this should either be confirmed in writing by the company or through “a corporate borrowing resolution giving authorization to that person.”

How & Why

(Information & Insight)

So we’ve established that credit applications are a tool for gathering information, but they serve a number of other purposes. For example, they can be a collections tool, as a legal document binding applicants to certain terms and conditions. Applications can also be used to monitor the creditworthiness of continuing business relationships.

Del Campo Supreme’s application asks for five trade references. While there are no rules governing trade references, Jimenez prefers business partners within the produce industry. “If [the applicant] gives me a trade reference for paying the water company, that doesn’t do much for me. I need a trade reference that they deal with daily,” she says. “I was in banking for 22 years, so I can see through the application and report whether a customer is going to be a good or bad risk to our company,” she adds.

Creating A Good Credit Application

According to Puru Grover, managing director of corporate credit and risk management solutions at Credit Guru in Toronto, Ontario, there are a number of elements that belong on every credit application. Here’s a quick reference list for purveyors of produce:

• Legal company name, along with any other “doing business as” or trade variations

• Type of business (sole proprietor, partnership, limited liability corporation)

• Sector or industry (some areas, such as the retail and service industries, tend to have higher rates of failure)

• Product or service type (this, too, adds to risk factors, i.e., bulk produce vs. fresh-cut or processed items)

• Number of years in this business sector

• Bank reference(s)

• Trade references – while three seems to be the typical number, some creditors request more and always ask for at least one from within the produce industry

• Website and applicant email address – can help authenticate a business and serve as valuable communication tools

• Terms and conditions – provide clear, concise wording of all terms and conditions

• Disclaimers – always include language detailing the following:

(a) permission to contact banks or financial institutions and trade references – both upon completion of the application and in the future;

(b) the applicant certifies information is true and correct to the best of his/her knowledge;

(c) upon signing, the applicant is bound by the terms and conditions set forth;

(d) a statement regarding allowable interest charges (which can vary by state of jurisdiction); and (e) that a faxed or scanned application can be deemed as original

• Signature – only an authorized individual (generally a company officer) is eligible to fill out and sign the credit application.

Outside Sources Provide Supplemental Information

Of course, every credit or finance manager would prefer a wealth of accurate information on every customer—but reality often dictates far less. “We don’t get perfect information,” concedes Brown. “We get incomplete information all the time, but we still have to make decisions. That’s why we try to confirm things by outside information or our historical records. We tend to look at things historically, factually, and unemotionally.”

As a result, Hapco Farms depends more on outside sources like Blue Book Services and looks to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Perishable Agricultural Commodities Act (PACA) for complaints, as well as checking business registrations with the Secretary of State. “Most of the time we don’t do applications,” Brown says, “but we do review customers when we see some unusual activity in the sales or payment pattern.” If pay is disrupted, he notes, “we’ll go back to Blue Book or if there is a credit application, we can call a vendor and see if anything has changed.”

Further, Brown notes, “Since economics are dynamic, things are changing all the time. We update our perspective on the customer regularly—that is, the amount of credit. That’s not something we do with an application, it’s something we do with the public record,” he explains, since an application can list “hundreds of thousands of dollars in a checking account, but what does that really mean? How fast can money leave a checking account? We review customers all the time, if not daily on an as-needed basis.”

This is where technology comes into play, and can be invaluable. Hapco subscribes to weekly credit updates from Blue Book and “mini reports” from other information sources. Michelle Johnson, the company’s senior credit analyst, will pour over listings, looking for Hapco customers.

This is where technology comes into play, and can be invaluable. Hapco subscribes to weekly credit updates from Blue Book and “mini reports” from other information sources. Michelle Johnson, the company’s senior credit analyst, will pour over listings, looking for Hapco customers.

Del Campo Supreme uses two other sources: Euler Hermes trade insurance and a proprietary system tied to the company’s ordering program. If a customer asks to raise its credit limit, Jimenez looks at pay patterns (such as nonsufficient checks) and if there are any PACA claims against the company. Then she will require a new application to see if the customer can handle the added amount. “We’re pretty strict,” she says, not only due to risk but because collateral is not an option. “We base about 90 percent of our decisions on what Blue Book has on the customer.”

Financial Reports

Credit managers agree on the value of a financial report to determine a customer’s creditworthiness. “Clearly the first and best source to make a good credit decision is based on financial statements,” Brown asserts. “We ask for them, but we don’t always get them.”

Though credit is important in all business sectors, it is much more of a concern in the perishable fruit and vegetable industry. It’s not particularly difficult to start a produce business, Brown notes. For example, in the PVC pipe business, a company would need to invest in a building, manufacturing equipment, and inventory. “That’s not the case in the produce business,” Brown says. “People can pick up the phone, call other people, and have trucks rolling with produce in them. So in terms of credit, it is a much more dangerous industry.”

Mitigating Risk

Giving customers credit keeps the produce business growing and moving, but establishing creditworthiness will never be a simple matter.

The companies that have mastered the process do so with a good credit application and prudent use of outside sources. These tools do not eliminate risk, but they can help mitigate the many pitfalls of operating in the fresh produce industry.