Orange Industry Summary

Image: dasytnik/Shutterstock.com

Orange Industry Overview

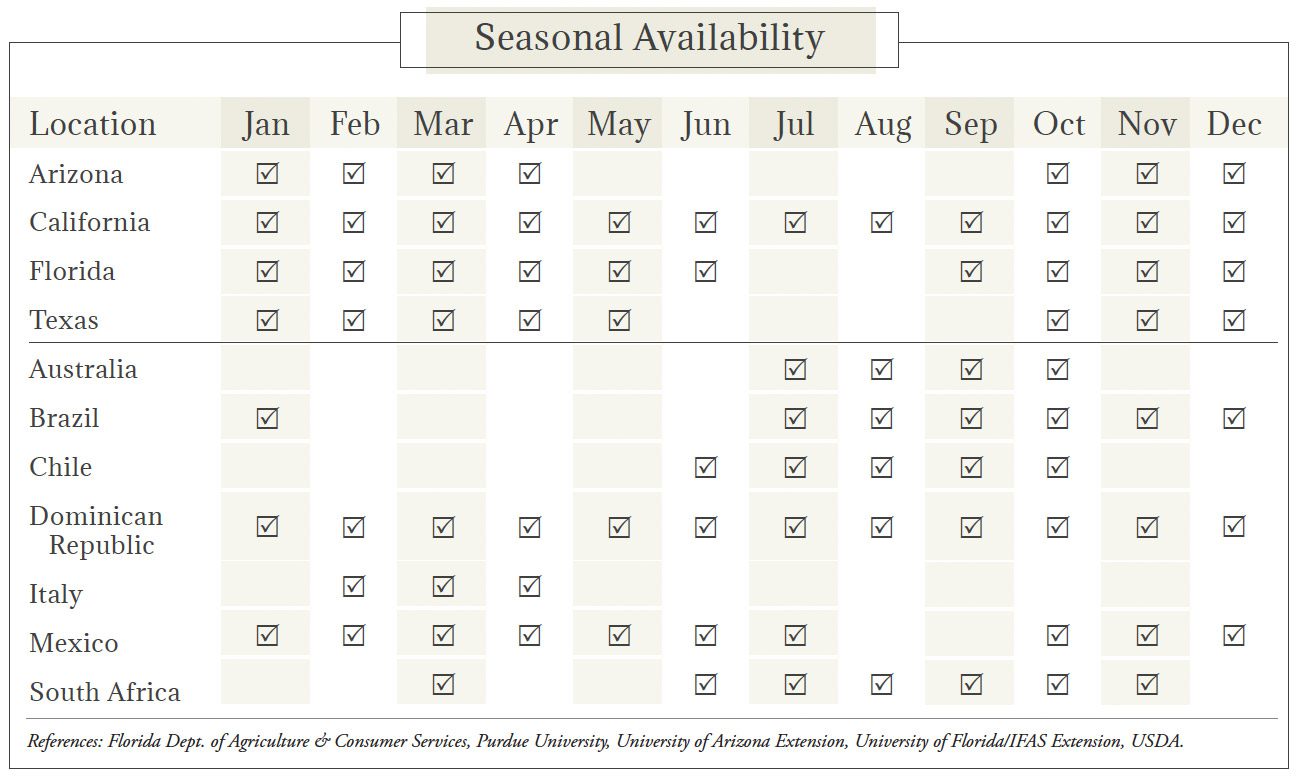

Oranges are one of the most ubiquitous crops in the world, grown throughout Asia, the Mediterranean, Africa, and both South and North America. The United States and Brazil are the world’s leading producers; most U.S. grown fruit is consumed domestically, while the bulk of Brazil’s output is exported. In the United States, top orange growing states are California, Florida, Texas, and Arizona. Florida continues to sustain major losses due to citrus greening; the disease has not materially affected California groves as of yet. Sunshine State production is divided between Valencia and Navel orange varieties. Oranges are believed to have originated from a wild variety in the Southern China/Northern India region, although these cultivars can no longer be found. Originally valued for medicinal purposes, oranges were brought to the Mediterranean region by Italian traders in the 1400s, then introduced around the globe by Portuguese explorers. The Spanish brought oranges to South America and to missions in Arizona and California, and the French brought them to what is now Louisiana. In the 1800s, orange groves were planted in Florida to much success.

Types & Varieties of Oranges

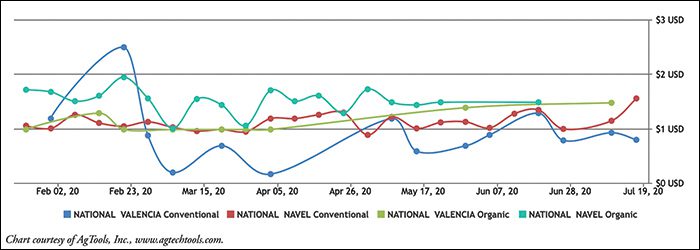

The bulk of U.S. orange crops consist of three main varieties: the Washington Navel, the Valencia, and the Hamlin, which are complemented by several other varieties such as the ‘Pineapple,’ Homosassa, and Queen. The Washington Navel has a thick, easy-to-peel rind and is easy to segment, making it one of the most popular eating oranges. It is not, however, a good variety for processing into juice, as a higher limonene content makes it bitter. Valencia oranges are smaller and juicier than Washingtons, with a thinner rind, and are popular for juice with few seeds. Valencias can also produce two overlapping crops each year. The Hamlin is similar to the Valencia—juicy and flavorful, but with lighter color fruit and juice. It’s seedless and also popular for juicing. ‘Pineapple oranges’ are a seedy, middle of the season variety with rich color and flavor, and Queens are similar, but hardier and able to withstand cooler and more dry temperatures. Blood oranges, so named for their red flesh and strong flavor, continue to gain popularity. They are grown selectively in Florida, but most are produced in the Mediterranean region. Another specialty orange is the bergamot, which looks more like a lemon or lime, and has an aromatic floral scent. Especially popular in Italy, bergamots are gaining favor with U.S. chefs.The Cultivation of Oranges

Orange trees need well-drained, loose soil as more restrictive soils can lead to root rot and shorten the life of trees. Many varieties are grafted onto other tree stock; newly planted trees can bear fruit in about 3 years. Oranges are still largely picked by hand, with mechanical harvesting used for juicing varieties. The challenge is getting the fruit to fall without damaging the tree, as oranges are firmly fixed to their branches. Some tests have been done using abscission compounds to weaken the stem and allow fruit to fall more easily, but are not in widespread use.

Pests & Diseases Affecting Oranges

Oranges are subject to several molds and rots, particularly after harvest, including green mold, blue mold, stem end rot, brown rot, and sour rot. Prevention includes proper handling to avoid physically damaging fruit, treatment with fungicides, rapid postharvest cooling, and proper storage temperatures. A serious challenge to orange growers is Huanglongbing (HLB), also known as citrus greening. Bacteria-based, it causes bitter and malformed fruit and eventually kills trees. It has been especially devastating in Florida and is spreading to other citrus-producing states. To address the problem, the USDA has been working with commodity groups and growers in an emergency response group, earmarking millions of dollars to find solutions. Citrus canker, another bacterial disease, was brought to Florida on hurricane winds in the 1980s and 1990s. It causes early fruit and leaf drop, as well as lesions on the fruit.Storage & Packaging of Oranges

Chilling injury can occur during storage at low temperatures where fruit can become pitted, stained, or suffer decay. Waxing or film-wrapping to maintain water content reduces incidence. Rind staining occurs when mature fruit is harvested late, but can be controlled by a preharvest application of gibberellic acid. References: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, Purdue University, UC Davis Postharvest Technology Center, University of Florida/IFAS Extension, USDA.Grades & Good Arrival of Oranges

Oranges grown in Arizona and California are divided into U.S. Fancy, U.S. No. 1, U.S. Combination, and U.S. No. 2 grades; for Florida oranges (and tangelos) the grades are U.S. Fancy, U.S. No. 1 Bright, U.S. No. 1, U.S. No. 1 Golden, U.S. No. 1 Bronze, U.S. No. 1 Russet, U.S. No. 2 Bright, U.S. No. 2, U.S. No. 2 Russet, and U.S. No. 3.

Generally speaking, the percentage of defects shown on a timely government inspection certificate should not exceed the percentage of allowable defects, provided: (1) transportation conditions were normal; (2) the USDA or CFIA inspection was timely; and (3) the entire lot was inspected.

ARIZONA & CALIFORNIA

| U.S. Grade Standards | Days Since Shipment | % of Defects Allowed | Optimum Transit Temp. (°F) |

| 12-7-3 | 5 4 3 2 1 | 15-8-5 15-8-5 14-8-4 13-7-4 12-7-3 | 38-48° |

FLORIDA

| U.S. Grade Standards | Days Since Shipment | % of Defects Allowed | Optimum Transit Temp. (°F) |

| 12-[7 VSD]- 3 | 5 4 3 2 1 | 15-[8 VSD]-5 15-[8 VSD]-5 14-[8 VSD]-4 13-[7 VSD]-4 12-[7 VSD]-3 | 32-34° |

TEXAS & OTHER STATES

| U.S. Grade Standards | Days Since Shipment | % of Defects Allowed | Optimum Transit Temp. (°F) |

| see standards | 5 4 3 2 1 | 15-[8 VSD]-5 14-[8 VSD]-5 13-[7 VSD]-4 11-[6 VSD]-3 10-[5 VSD]-2 | 32-34° |

Inspector's Insights for Oranges

- Skin breakdown, usually a sunken pitted area found around the stem end, is scored as a defect when affecting an area greater than a quarter inch on California oranges or greater than half an inch on Florida oranges

- Smooth scars, affecting more than a third of the surface are scored as ‘excessive discoloration’ on Florida oranges

- Dryness or mushy conditions from freezing injury is scored as a defect when affecting all segments more than a quarter of an inch at the stem end, or the equivalent by volume.