Mangos Market Summary

Image: JIANG HONGYAN/Shutterstock.com

Mangos Industry Overview

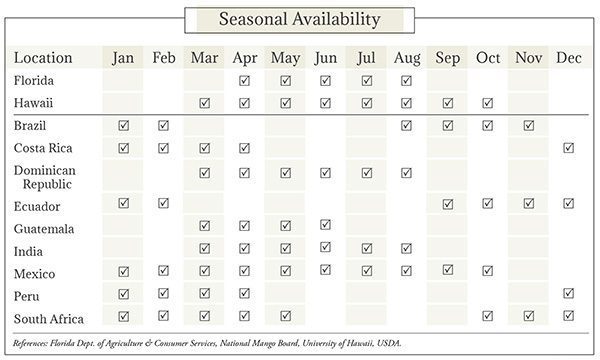

Mangos (Mangifera indica) were cultivated in India over 4,000 years ago. Known as the “fruit of the gods” or the “queen of fruits,” mangos were widely consumed throughout Southern Asia. Mangos eventually made their way via trade to Africa, Asia, Europe, and finally to the Americas. The earliest mangos were introduced and successfully cultivated in Florida in the early to mid-1800s. The Haden mango was the first commercially grown crop in Florida. A member of the Anacardiaceae family, the mango tree is a relative of poison ivy, poison oak, and sumac—which means the plant produces urushiol, a chemical that causes an itchy rash. Luckily, mangos only produce small quantities, so even those who are sensitive to urushiol can usually consume the fruit’s flesh. The leaves of the tree, however, are toxic and can be harmful to animals. Eaten both ripe and unripe, mangos are also dried and powdered to be sold as amchur, an Indian spice. Various traditional products include raw mango slices in brine, pickling the fruit, creating various preserves, and making chutney. Mangos are also lauded for their medicinal properties. Over the last few decades, mangos have slowly earned a spot in the limelight in North America. About 90 countries grow them commercially, with more than three-quarters of the world’s production occurring in Asian countries, including India, China, Thailand, and Pakistan. Mexico, too, cultivates a significant portion of commercial production. Africa and the Americas make up a very small portion of global supply. Within the United States, mangos are grown in Florida and California. They are also grown in Hawaii (but can’t be exported to the mainland, see below) and Puerto Rico. Most mangos consumed in the United States are imported from Mexico. Smaller amounts are imported from Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Guatemala, and Haiti. Globally, market prices for mangos vary from country to country, with the cheapest prices in Indonesia and Thailand and higher prices in India. Prices in the United States are highest in February and March when availability is low.

Types & Varieties of Mangos

While the exact number of mango varieties is uncertain, there are at least 500 and perhaps as many as 1,000 with 350 grown commercially worldwide. The USDA reportedly documented over 500 different mango varieties from India, the Philippines, and the West Indies, just between 1899 and 1937. Others have proliferated in the decades since. Mangos have a characteristic fragrance and smooth, thin, tough skin. Shape ranges from round to oblong and mature fruit can weigh from under a pound to 2 pounds. Depending on variety and ripeness, mature fruit can be yellow, orange, purple, red, or combinations of these colors. Flesh is sweet and fibrous. In India, the world’s largest producer, mango types are usually classified as early, early to mid-season, mid-season, mid-to-late season, and late-season. Common early-season mangos are Bombay Yellow, Malda, Pairi, Safdar Pasand, and Suvarnarekha. Early to mid-season are Langra and Rajapuri. Mid-season types include Alampur Baneshan, Alphonso, Bangalora, Banganapally, Dusehri, Gulab Khas, Zardalu, and K.O. 11, with mid-to-late season Rumani, Samarbehist, Vanraj, and K.O. 7/5. Late-season types include Fazli, Safeda Lucknow, Mulgoa, and Neelum. Because of alternate harvest times, mangos are generally available to U.S. receivers year-round. Domestically, Florida’s production runs from May to September. Top sellers in the United States vary by size, color, and firmness. The roundest variety is Haden, with bright yellow flesh and a firm texture. American consumers tend to prefer mangos with a reddish blush to the skin. Kent is a soft, oval-shaped mango with a distinct tropical flavor. Tommy Atkins is shaped like Haden, but with a less robust flavor. The largest mango variety is Keitt, completely green with a hint of yellow when fully ripe. The Francisque mango from Haiti is medium-sized and flat. There are two small varieties of mangos: Van Dyke and Ataulfo (rebranded as ‘Honey’ by the U.S. National Mango Board). Van Dykes have a pineapple-like flavor while Honey mangos are very sweet.

Cultivation of Mangos

Mango trees are evergreens that can grow from about 30 to 100 feet tall. Commercial growers often trim and maintain the trees at about 20 feet for ease of access and better sunlight penetration. Canopies can grow as wide as 75 feet or more. Mangos can grow in a range of soil types. Soil should be well-drained with ample irrigation, which is crucial for mangos to thrive in lowland subtropical and tropical climates, particularly while establishing seedlings. Some growers prefer to plant mango trees on slopes to promote drainage and prevent excess moisture absorption. Commercial mangos are most often propagated through grafting onto rootstock. Trees produce long leaves from 12 to 16 inches in length. Small white flowers will appear in clusters known as panicles. Little pollination is from bees, most is from butterflies, moths, beetles, ants, and even fruit bats. Rainy weather may discourage flowering of trees and heavy rains may disturb pollen and prevent the fruit from setting. The amount of rainfall is not as important as the timing of its occurrence. While ideal rainfall for mango trees depends on location, it can range from 30 inches to as much as 100 inches, especially during hot summer months. Most trees are still able to flourish during periods of dry weather or in areas of sporadic rain. After pollination, fruit develops after three to six months, depending on type. In most commercial varieties, only one fruit emerges per panicle. Established growers can fit about 100 trees per planted acre, yielding from 165 to as many as 440 pounds of mangos per tree. Trees are usually spaced 10 to 30 feet apart with 20 to 30 feet between rows. Trees younger than 10 years old tend to bear fruit yearly, while older trees tend to bear fruit biennially, for 40 years or more. Pruning is not necessary for growth, but generally done two to four times a season after harvest to allow better access for spraying and subsequent pickings. While newly planted trees require ample water for the first couple of months, mature trees do not except during very dry periods as mentioned above. Fruit is usually picked by hand when mature but slightly unripe to better withstand shipping. Ripe mangos are generally yellow, orange, and red; skin ripens to yellow if mangos are in the shade and red when exposed to full sun. The fruit is usually picked with the stem intact, and stored stem-end down, to ensure juice does not leak, or drip on other fruit.

Pests & Diseases Affecting Mangos

Poor preharvest practices or postharvest handling can cause a range of issues for mangos, from skin abrasions and chilling or heat injury to softening of the flesh. Powdery mildew is common in Florida in March and April and causes young fruit to dehydrate and fall from trees, leading to losses of up to 20% in yields. Anthracnose is also common in humid climates, affecting flowers, leaves, twigs, and fruit, causing black spots. Mangos are also vulnerable to scab, leaf spot, wilt and verticillium wilt, sapburn, stem-end rot, and witch’s broom. Pests of concern include aphids, beetles, mites, thrips, mealybugs, whiteflies, blackflies, and nematodes. In Florida, the most common pests are mites, scale, thrips, and ambrosia beetles. Fruit flies are a common problem in certain regions and affect the importation and distribution of commercial mangos. Hawaiian-grown mangos are not allowed on the U.S. mainland due to fruit flies and weevil concerns.Storage & Packaging of Mangos

Exposure to ethylene speeds up the ripening process, and takes from 5 to 9 days depending on the type of mango and the level of ripeness for the fruit. Ethylene treatment helps ensure more uniform color and usually takes about 24 hours of exposure to achieve. Mangos should not be stored in direct sunlight after harvest to avoid accelerated ripening and shortened shelf life. Dirt and juice should be removed from fruit, as juice on the skin can lead to black lesions and encourage rot. Hot water treatments protect mangos from fruit flies, while hydrocooling will reduce flesh temperature and limit injury to the fruit. Some mangos are coated in wax to reduce water loss during shipment and enhance the skin’s gloss; others are wrapped in plastic film to prevent decay. Ripening can be delayed by cold storage. Proper ventilation is important to maintain uniform temperature and humidity levels during storage and shipping. Optimum storage temperatures are 55°F for mature green mangos and 50°F for partially or fully ripe mangos with 90 to 95% relative humidity. Lower temperatures can cause chilling injury; higher temperatures, above 75°F, can lead to shriveling and affect flavor. References: National Mango Board, Purdue University, University of Florida/IFAS Extension, University of Illinois Extension, University of California, Davis, USDA.Grades & Good Arrival of Mangos

Mangos are divided as U.S. Fancy, U.S. No. 1, and U.S. No. 2: Fancy requires fruit be of similar varietal characteristics, mature, clean, well-formed, not overripe, and free from decay, discoloration, skin breaks, bruising, scabs and scars, shriveling or sunken areas, russeting, disease, insects, and freezing or mechanical injury. For U.S. No. 1, the above applies though fruit should be fairly well-formed, not overripe, and free from damage caused by decay, discoloration, skin breaks, and damage caused by bruising, scabs and scars, shriveling or sunken areas, russeting, disease, insects, and freezing or mechanical injury; U.S. No. 2 follow U.S. No. 1 requirements differing only in allowing no serious damage from bruising, scabs and scars, shriveling or sunken areas, russeting, disease, insects, and freezing or mechanical injury.Generally speaking, the percentage of defects shown on a timely government inspection certificate should not exceed the percentage of allowable defects, provided: (1) transportation conditions were normal; (2) the USDA or CFIA inspection was timely; and (3) the entire lot was inspected.

| U.S. Grade Standards | Days Since Shipment | % of Defects Allowed | Optimum Transit Temp. (°F) |

| 10-5-2 | 5 4 3 2 1 | 15-8-4 14-8-4 13-7-3 12-6-2 10-5-2 | 55° |

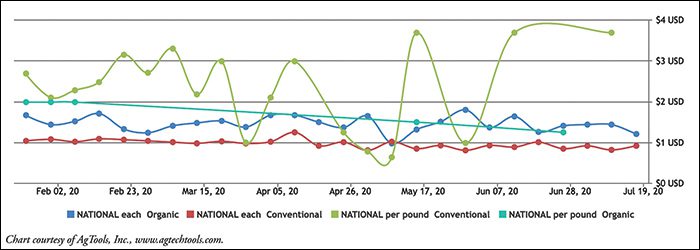

Mango Retail Pricing: Conventional & Organic

Varietal Showcase: Ataulfo MangosAtaulfo mangos, sometimes called Honey, are lauded for their sweet-and-sour taste, often described as having a peachy undertone. Their shape is oblong, slightly pointy, and the fruit is small in size compared to other varieties.

When ripe, the fruit’s skin turns from a yellowy green to vibrant gold with tiny wrinkles. Inside, the flesh is smooth, creamy, juicy, and fiberless.

Although mangos originated in India centuries ago, the Ataulfo can trace its more recent ancestry to Southeast Asia in the Philippines. It is a descendant of a mango called the Philippine, Carabao, or Manila, and was first cultivated in Chiapas, Mexico, by grower Ataúlfo Morales Gordillo.

Ataulfo mangos enjoy warm, humid growing locales and are available year-round from Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil, peaking from March to July/August.

|

Varietal Showcase: Mallika MangosMallika mangos are a hybrid originating from India, a cross between Neelum and Dasheri varieties. They are known for their exceptional sweetness with rich, creamy pulp.

Mallika mangos grow well in tropical and subtropical locales. They are large, flat, and slightly elongated with smooth yellow skin when ripe. The Mallika is known for its uniquely sweet flavor with hints of citrus, melon, honey, or vanilla. The flesh is orange, juicy, and nonfibrous, making it ideal for eating fresh or added to smoothies, chutneys, salads, and desserts.

Fruit is harvested when mature and green to ripen off the tree. Once ripe, the skin turns yellow and the mango emits a fruity yet floral aroma. Frequently marketed as a premium product, Mallikas are prized by mango devotees for their distinctly delicious flavor and silky texture.

|