When fresh product arrives at destination warm, some predictable and unpleasant things tend to happen: first, the receiver objects.

The receiver doesn’t want warm product that will spoil prematurely on its (or its customers’) shelves—and for sure, the receiver doesn’t want to pay full price for it.

Second, the finger pointing starts. The shipper alleges that the carrier failed to maintain proper temperature control, and the carrier alleges the shipper loaded warm product.

And third, the parties tend to spend a fair amount of time investigating facts, debating responsibilities, and trying to settle the offending transaction without further straining the business relationship.

In this article we discuss how Blue Book’s Trading Assistance team approaches these disputes, and best practices for managing or avoiding these disputes in the future.

Diligence at Shipping Point

As a starting point, it’s important to acknowledge that in the long history of the produce industry, more than a few shippers have been guilty of deliberately loading old warm product in a trailer with the intention of blaming the warm temperatures and condition problems discovered at destination on the carrier.

Thankfully, this kind of practice seems to be far less common today than in the past. But we still occasionally see what look to be pretty blatant examples from time to time.

And, of course, an oversight at shipping point, even from an entirely scrupulous shipping warehouse, may result in similar problems upon arrival at destination.

Consequently, carriers should be vigilant at shipping point and verify pulp temperatures from multiple random samples throughout the load.

If no pulping is permitted, we would recognize a carrier’s right to refuse to take the load provided this was not discussed (or known) in advance.

Although we rarely see it, in theory, the carrier could sign the bill of lading “shipper’s load and count” or “no pulping permitted” to make sure that a clean bill of lading isn’t later used against it.

When carriers throw caution to the wind and simply sign the bill of lading “clean” at shipping point, this may later be interpreted to mean either: (1) the pulp temperatures were good; or (2) the carrier had no firsthand direct knowledge of warm pulp temperatures at loading.

Conversely, shippers can usually be expected to point to the clean bill of lading and their firsthand knowledge of their loading procedures as direct evidence of proper precooling (e.g., an affidavit from operations personnel and/or internal records such as a load sheet with pulps).

And while this type of evidence is not ironclad, it tends to be stronger than the carrier’s indirect evidence.

What’s more, it tends to be strong enough to make the shipper’s prima facie showing and shift the burden of proof onto the carrier to prove “freedom from negligence” and shipper error under the common law of common carriage.

Of course, when we have to start talking about prima facie showings and burdens of proof, the transaction has already gone sideways.

Shippers that provide load sheets with pulp temperatures verified by the carrier’s driver tend to avoid a lot of unnecessary friction in these scenarios.

Freedom from Negligence

When assessing freedom from negligence it is important to remember that while air temperatures in transit affect pulp temperatures, strictly speaking, carriers are only responsible for maintaining air temperatures in the trailer.

So, warm pulp temperatures at destination do not necessarily mean the carrier cannot prove freedom from negligence.

But carriers will need to rely heavily on temperature readings from the portable recorder and reefer unit to prove freedom from negligence and show the shipper errored by loading warm produce.

Complicating matters somewhat is the fact that warm product temperatures will affect the surrounding air temperatures in the trailer.

Taken to an extreme, a full truckload of extremely warm product could, in fact, cause freezing of the top layers of the rear pallets as the reefer unit blows colder and colder air trying to regulate the return air readings in the nose of the trailer.

In a less extreme scenario, when product is loaded warm, we typically expect to see warmer readings on the portable recorder during the first day of the trip, with temperatures normalizing as field heat dissipates and the rate of respiration slows (respiration rates generally slow within 24 hours after harvest).

This type of pattern to the air temperature readings can go a long way in support of a carrier’s denial of a claim.

Conversely, when temperature recorders indicate that air temperatures were warm or increasing well into the trip or were rising and falling with the outside temperatures (warming significantly during the afternoon and evening hours), these patterns do little to help the carrier meet its burden of proving freedom from negligence and shipper error.

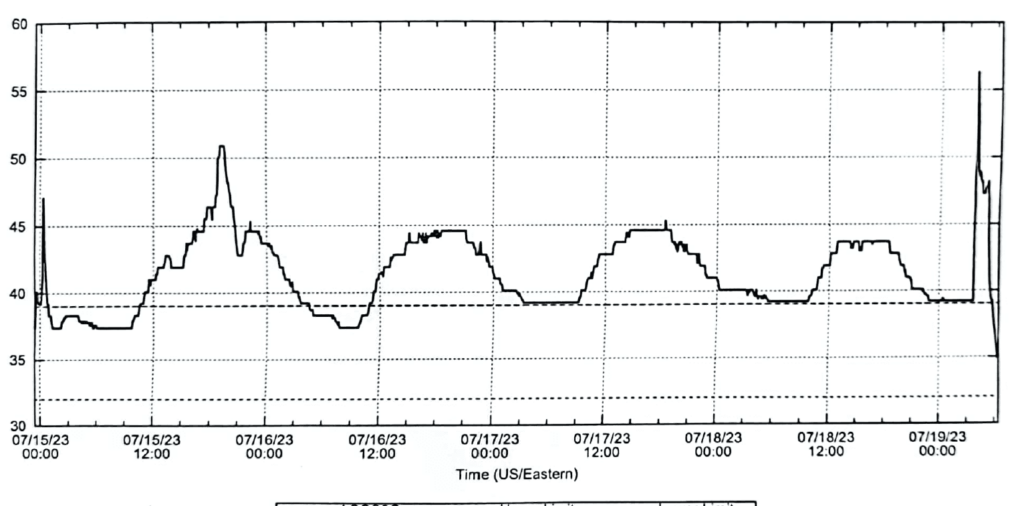

In this temperature graph (from a shipment where the instructed temperature was 34°F continuous), we see that air temperatures in the trailer stabilized between 36 and 37°F for close to 10 hours during the first morning.

Had temperatures remained in this range and normalized further during the later days of the trip, this initial temperature variance, in our view, would be consistent with a carrier’s suggestion that the product was loaded warm, and that it was “free from negligence.”

Unfortunately, however, that’s not the story the readings tell as the trip progresses.

Rather than seeing improving temperature control as any heat from the product dissipated and respiration slowed, we see the readings began to climb over the next 10 hours to over 50°F—far beyond what can be considered a normal variance.

The remainder of the trip shows a similar though less extreme pattern, where the readings fluctuate significantly with the warmer readings occurring in the afternoon and evening hours.

These readings are simply inconsistent with a carrier’s suggestion that the temperature control issues were caused by warm pulp temperatures at loading.

Even product that was loaded warm gives off less heat over time, and at least in our experience, never enough to overwhelm a properly functioning reefer system (i.e., the reefer unit and a well-insulated trailer) in the later days of a long-haul trip.

Conclusion

We believe it is in the best interest of shippers to allow carriers to fully validate pulp temperatures at shipping point to reduce the frequency and complexity of these disputes.

Clearly it is in the best interest of carriers to do so; a carrier that signs the bill of lading “clean” without validating pulp temperatures is taking unnecessary risk.

As we can all agree, it’s far better to raise concerns about warm product at origin, than at destination after the damage has been done.

This is a Trading Assistance column from the September/October 2023 issue of Produce Blueprints Magazine. Click here to read the whole issue.