There is vertical, and then there is vertical.

This enigmatic utterance reflects some differences—and possibly shakeouts—in the world of vertical farming, of which, strictly speaking, there are two types.

There is stacked vertical. This consists of rows of horizontal trays stacked atop one another.

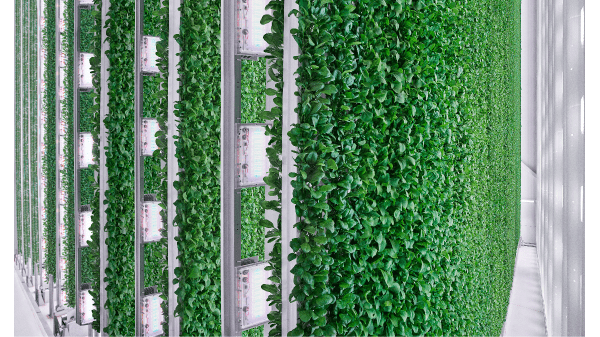

Then there is “true” vertical: that is, the growing bed itself is vertical, at (more or less) 90 degrees.

“As the vertical farming industry works to move from the startup to scale-up stage, we predict there will be a shakeout between ‘stacked tray’ vertical farms and truly vertical farms,” contends Nate Storey, cofounder and chief science officer of Plenty BB #:382600, a company devoted to developing and growing on “true” vertical farming systems. “Why? The claimed benefits of stacked-tray vertical farming simply don’t stack up. It’s basic physics. And it’s going to lead to more failures in the ‘vertical’ farming space in the coming months and years.”

One reason, Storey says, is that horizontal trays trap heat. “That limits the intensity of the lights that stacked vertical farms can use, which puts a cap on yield since more light equals more photosynthesis, which equals more yield. As a result, stacked vertical farms have limited levers to pull to increase yields.” Furthermore, there are limits to efficiency gains in LED lighting technology.

Consequently, it takes more surface area to grow a given amount of produce under lower light than under higher light.

“Lastly,” says Storey, “stacked tray systems struggle to support crops outside of leafy greens at mass commercial scales.”

Storey goes on to say, “By contrast, a true vertical approach changes the orientation of the growing plane. True vertical farms maximize the density of plants in a three-dimensional space by growing on massive, uninterrupted vertical growing planes, placed back to back (in Plenty’s case, on both sides of vertical grow towers nearly two stories high).”

Plenty’s true vertical system can produce up to six times as much yield as stacked-tray systems, Storey contends, largely thanks to ultra-intense lighting.

“Air circulation in wide vertical aisles (that double as access) is efficient, simple and assisted by convection,” he adds. “Plenty’s true vertical system has a modular, flexible architecture that can support a wide variety of plants and introduce crop diversity. We’re the only true multi-crop platform in indoor ag, assisted by the precise temperature and humidity control we have over our environment.”

The versatility of true vertical will be increasingly useful in coming years, when world food needs will require growing more caloric crops on a denser scale, Storey says. His company has already grown 50 different crops and 1,400 cultivars with its system.

Next year Plenty plans to grow strawberries on a commercial scale with its vertical approach. The 120-acre farm will be located outside Richmond, VA.

Plenty chose strawberries because presently, market demand exceeds supply. Moreover, Storey adds, “strawberry quality and pricing fluctuates dramatically throughout the year, whereas production in our farms can be constant and predictable in terms of quality and cost.”

In addition, “out-of-season berries are often shipped halfway around the world to reach consumers, with an unexpected impact on quality. Growing strawberries better than the best land, anywhere in the world is a dramatic demonstration of what indoor agriculture can do for local production and food security.”