December 9, 2020 – Monterey, CA – Leaders from three of the largest and most respected organic fresh produce companies agree that the outlook for the organic industry is positive heading into the new year, as they explored a wide range of issues during the Organic Grower Summit BB #:338018 Roundtable discussion that premiered today.

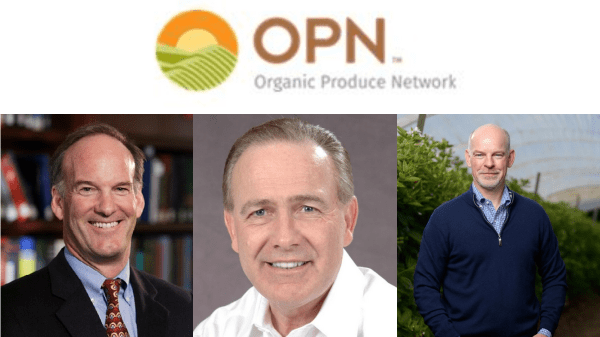

Moderated by Dave Puglia, president and CEO of Western Growers Association BB #:144734, the roundtable featured Bruce Taylor, president of Taylor Farms/Earthbound Farm BB #:193361; Soren Bjorn, president of Driscoll’s of the Americas BB #:116044; and Vic Smith, president of JV Smith Companies.

Puglia kicked off the discussion asking the three leaders about the effects this tumultuous year has had on the industry and what things might look like in 2021.

After a couple months of “extreme anxiety” following the onset of the coronavirus crisis, Smith said his company, which is a major grower of leafy greens, was able to “shift gears” and adjust to the lack of foodservice demand and the increased demand at retail.

Taylor, whose company sells to foodservice, deli, and retail, said that at the start of the pandemic, foodservice demand “went to zero,” with the deli segment following suit a little later. While increased retail demand helped offset these losses, Taylor noted that the differing types of demand among the segments caused some issues.

“The quick-service restaurants consume quite a bit of iceberg lettuce,” said Taylor. “And so the demand pattern shifted. … We’re going, ‘Oh, what the heck? What do we do now with all this product?’ And so we had about a $70 million pile of vegetables out there to work through in a 10-week period of time. And our team did a nice job doing it—but that was a huge challenge. And so even today, the challenge is, what do I plant?”

Bjorn characterized the early days of the pandemic as “pretty worrisome. We were throwing berries away in April,” he said. “But by the time we got into the summer, it’s been really, really strong.”

Going forward into 2021, Bjorn said Driscoll’s volume will be influenced by decisions they made last spring when the outlook hadn’t seemed as robust (berry production is planned about a year in advance).

“We were not very aggressive back in April in our thinking, and that’s probably going to come back to haunt us a little bit in 2021,” he said. “There’s really nothing we can do to increase the supply for next year. Ideally we would have, but that should make for, I suspect, pretty good markets in 2021.”

Noting that all three leaders have been in organics for a long time, Puglia asked them their thoughts on the sector’s place in the produce industry and how it’s evolved over the years.

Both Taylor and Bjorn remarked that large-scale organic farming is now critical to meeting consumer demand and to maintaining an economically viable business. “It takes large-scale agriculture in many cases to create those economies that can then reduce the price and increase the availability to people across the country,” said Taylor.

“If you don’t have the larger companies like ours … [organics] won’t be widely available. It will be for the few,” said Bjorn. “We think that it should be for the masses. And clearly the consumers are very clear—they want it to be for them. … They want organic to be part of a healthy lifestyle. And in the berries, it’s growing way faster than conventional—probably three or four times faster.”

Smith said he’s seen organic agriculture have a positive influence on conventional operations. “[It] taught us we’re putting a lot more fertilizer in the ground than I think we need because we were growing head lettuce using 140 units or 200 units of nitrogen for conventional. And we’re over there spoon-feeding this stuff in organic—not getting the full size but pretty close at about 80 units. And you go, ‘Wait a minute, do we need to use that much [in our conventional operations]?’ So I think it was a good perspective for us to understand what we were doing and how.”

Taylor agreed: “In Europe, the difference is very small now, from what I understand, between organic and conventional [in terms of] respect for the soil and, just like you said, the different tools you use and the way you go about it.”

Not mincing any words, Bjorn said, “Our best organic growers are our best growers. Period.” He noted that the lack of conventional ag tools forces organic farmers to be more vigilant. “[They’ve] really got to pay attention, and it just makes them better growers,” he said. “And so, yeah, for sure, they take that back to their conventional practices. And so you see a lot more blending.”

In a particularly lively part of the discussion, the three leaders talked about the rise of indoor growing operations as a potential threat to organic market share.

“The coming competition to organic is indoor grown—whether it’s greenhouse or vertical farming—and the attraction there is local,” said Taylor. “You’ve got this huge amount of capital going into building greenhouses around the United States. And there’s no organic protocol. … There’s no standards that they need to adhere to. It’s just they go to market as local, and the consumer prefers local over organic. … And so that’s just something to keep our eyes on.”

Bjorn agreed, adding, “We [at Driscoll’s] obviously look at it as an opportunity because we have put some money into it. … We recently announced that we are doing a partnership with Plenty, an indoor farming company out of San Francisco. … When you look at the economics of indoor farming, you have these drivers—just like you have when you’re farming outdoors—the drivers of the economics. And so obviously transportation is a big, big factor, right? So in leafy greens, sometimes the freight is more than the leafy greens. But if you eliminate the freight, we [save] that money.”

Bjorn went on to share that Driscoll’s had to start chartering planes to get its berries to the Middle East when passenger flights dropped off due to the coronavirus. He said the freight has become so expensive that building an indoor farm in the region now seems like a cost-effective endeavor. Bjorn also cited oil costs (which have the potential to rise), organic regulations, and the risk of bacterial contamination as other reasons why indoor farming might be a more economical choice.

Bjorn said the main reasons consumers buy organics is because they are pesticide free and are perceived as more likely to be local. “Well, indoor farming addresses both of those issues because it will be super local—you can stick the farm right next to where all the people are. … And you don’t use any pesticides inside. So the very thing that makes organics such an attractive business, the indoor farming actually addresses.”

Smith expressed some skepticism about the economic viability of indoor farming. “I’m biased because I do a lot of growing in Western soils. And I look at [indoor farming], and I just can’t see in the next 20 years how they’re going to beat the efficiency factor that we have,” he said, citing electric trucks as an answer to any future spike in oil price.

Puglia wrapped up the session with a lightning round, asking the three leaders if they were bullish or bearish on organics 10–20 years from now.

“I’m bullish,” said Smith. “But I expect that we’re going to have to get better and better as producers of organic. I think we’re going to have to be very nimble and react to consumer expectations.”

Taylor shared that he was “cautiously optimistic,” citing an increase in consumption by the younger generation as his reason for optimism and the consumer’s penchant for flavor as his reason for caution. “To the extent … the organic industry can produce product that tastes great, [it’ll] thrive,” he said. “But [it is] threatened by others that are pushing the taste envelope and the quality characteristics.”

“I’m definitely bullish,” said Bjorn without hesitation. “I think this is where consumers want to go. And it’s always good advice to follow the consumer if you want to be in business.”

Media Contact:

Matt Seeley

831-884-5092

matt@organicproducenetwork.com