Retail grocery has seen convulsive shifts as a result of the coronavirus. But how permanent are they?

A study recently released by the Nielsen research agency covering 15 countries shows “clear declines” in grocery retail spending “in high-density areas, such as downtown districts filled with offices and commuter hubs.”

Before the coronavirus, the study explains, people tended to shop on their way home from work, buying food from stores close to train stations or near office parks.

Spending in these stores has dropped radically. Instead people have been shopping more in residential areas. “Behind the $85 billion, or 12% in year-to-date U.S. sales growth, is a story of local behavior shifts that has grown the pool of top stores that should be on the radars of retailers and manufacturers,” says Nielsen.

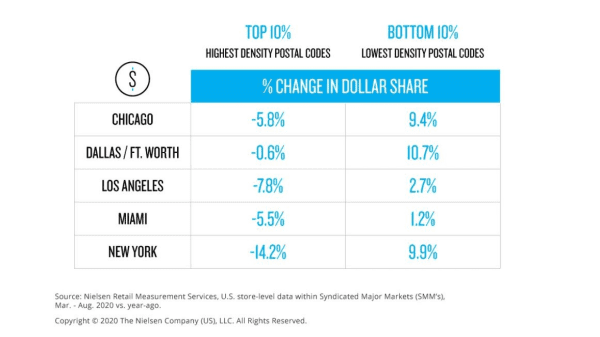

“Stores aligned to high-density workplaces are no longer within reach to many new remote workers,” says Nielsen. “In fact, across five key U.S. cities, CPG [consumer packaged goods] dollar share has declined swiftly among stores located within the highest density postal codes and risen among stores within the lowest density areas.”

In Manhattan, for example, sales dropped over 37 percent in the period from March to October. In Chicagoland, sales in the highest-density zip codes dropped 5.8 percent in March through August (compared to the prior year), while sales in the lowest-density zip codes rose 9.4 percent.

The study also found that in high-growth areas, consumers were using grocery stores to fulfill a wider variety of needs. “Comparatively, consumers have relied less exclusively on grocery stores to meet their shopping needs in the postal neighborhoods that are experiencing overall sales declines.” Presumably this means increased use of online shopping, among other trends.

Will these trends continue after the virus has abated?

Scott McKenzie, Nielsen Intelligence Unit leader, says they will: “Companies around the world are already signaling they will no longer operate the way they did in the past. People will commute less, work from home more and move further away from city centers. The consequences of this for the locations of stores, the formats of stores, the assortment in those stores, and of course, the pricing of products are far reaching. If you add in the dynamic of a massive rise in e-commerce for the FMCG [fast-moving consumer goods] space, the need to respond to what we have discovered is one of urgency.”

How long-lasting are these trends? It’s probably true that working remotely will remain far more common than it was a year ago. Nonetheless, this doesn’t necessarily mean major population shifts from the city to the suburbs.

“I think it’s possible that we’ll have a short-term shift in the demographic . . . for a few years,” says Jessie Handbury, a real estate professor at the Wharton School of business. “But I do think this is not going to be dramatic, and it’s not going to be a reversal of the trends that have been seen over the past 10 or so years.”

Handbury says that in the long run, major urban centers will continue to attract recent college graduates and young professionals. This will more than offset the number of older people who are fleeing the cities for the suburbs.

Like most COVID trends, this scenario leaves many open questions. Clearly people are cooking at home far more than they were before the pandemic. As it abates and things return to normal, will remote workers stick to their kitchens, or will they drift back to restaurants? On the answer to that hangs the survival of much of the foodservice sector.